5 Cognitive imagination

Many authors contrast sensory imagination with cognitive imagination (“imagining that,” or “propositional imagination”), which has been defined as belief-like (Mulligan 1999; Currie & Ravenscroft 2002; McGinn 2004; Goldman 2006; Weinberg & Meskin 2006b; Arcangeli 2011a).[17] Cognitive imagination seems to be relatively autonomous from sensory imagination. For instance, one can imagine that poverty has been reduced in the world independently of re-creating any visual, auditory, tactile, etc., experience. Of course the autonomy of cognitive imagination relative to sensory imagination echoes the autonomy of belief relative to sensory perception (one can believe that poverty must be reduced in the world without perceiving anything).

Cognitive imagination is by essence non-sensory, but given our previous discussion, it does not exhaust the field of non-sensory imaginings. Re-creating in imagination some internal experience is presumably non-cognitive (in the relevant sense of being belief-like), but it is non-sensory as well. Thus we have, at least prima facie, three types of potentially dissociable imagination: sensory non-cognitive imagination (e.g., I imagine hearing a piece of music, such as Ravel’s Concerto pour la main gauche), non-sensory non-cognitive imagination (e.g., I imagine having the proprioceptive experience of being one-armed), and non-sensory cognitive imagination (e.g., I imagine that Maurice Ravel has created a piano piece especially for me).

One might argue that cognitive imagination is not only non-sensory but non-experiential as well and as such lies outside the scope of GH. According to a standard view, beliefs, even if they can be occurrent, are not conscious experiences strictly speaking. On this view, an occurrent belief may be accompanied by various experiences (mental images, feelings, emotions, etc.), but there is nothing it is like to have a belief.[18] Now this view has recently come under attack by philosophers who acknowledge the existence of a doxastic phenomenology, i.e., a kind of phenomenology characteristic of belief (see the debates on cognitive phenomenology in Bayne & Montague 2011). On this alternative view, there is something it is like to have an occurrent belief, which is reducible to neither sensory nor affective phenomenology. At least some occurrent beliefs would be sui generis conscious experiences.[19]

If the alternative view is broadly correct, some beliefs lie within the scope of GH.[20] In order to capture cognitive imagination as a putative form of experiential imagination, let us introduce another specific hypothesis subordinate to GH, which we call the Cognitive Hypothesis (C):

CogH =Df To imagine something cognitively is always at least to re-create a conscious occurrent belief.

For instance, cognitively imagining that quantum physics is false or that this pen is an alien involves re-creating the conscious occurrent belief that quantum physics is false or that this pen is an alien. In general, one may surmise that anything that can be consciously believed can be cognitively imagined.

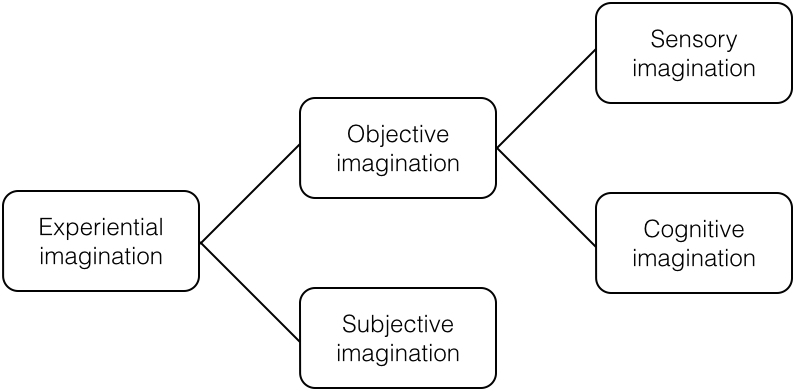

We have suggested that experiential imagination divides into two sub-domains only, namely subjective and objective imagination (covered by SubjH and ObjH, respectively). In addition, sensory imagination (covered by SensH) emerged as a species of objective imagination and non-sensory non-cognitive types of imagination (e.g., proprioception-like and agentive-like imagination) have been described as paradigmatic cases of subjective imagination. What about cognitive imagination (covered by CogH)? Is it a type of objective or of subjective imagination? Or should we acknowledge a third class of experiential imaginings that are neither objective nor subjective?[21]

We have introduced the distinction between objective and subjective imagination as the imaginative analogue of the distinction between external and internal experience. As we have seen, many external experiences are ways of gaining information about the world, and many internal experiences are ways of gaining information about oneself. Now one might claim that belief, unlike perceptual or introspective experience, is not individuated in terms of ways of gaining information. Of course some of our beliefs result from various ways of gaining information about the world and ourselves, but it is logically possible to have a belief that is not the result of any source of information. Does it follow that belief as an experience is neither external nor internal? Not really, for an external experience has been more fundamentally defined as being accidentally de se, whereas an internal experience is essentially or at least normally de se. In this more fundamental sense, if belief is an experience, it is clearly an external experience: one can believe all sorts of states of affairs that do not involve or concern oneself. It follows that cognitive imagination, as the re-creation of an external doxastic experience, is better seen as a sub-species of objective imagination, along with sensory imagination. Objective imagination then emerges as a heterogeneous domain, but where at least two clearly different types of imagining can be distinguished (see figure 3).

Figure 3: The varieties of experiential imagination

Figure 3: The varieties of experiential imagination