3 Objective and subjective imagination

Peacocke himself intends GH to cover genuine instances of experiential imagination that are not covered by SensH—what we shall call non-sensory imagination. For instance, one can imagine “the conscious, subjective components of intentional action” (Peacocke 1985, p. 22). On Peacocke’s view, imagining playing the Waldstein sonata may involve re-creating a non-sensory experience, namely the intimate experience one has of one’s own action while or in acting.

Of course, the precise nature of what we may call “motor imagery” is controversial.[6] Currie and Ravenscroft suggest that “motor images have as their counterparts perceptions of bodily movements. They have as their contents active movements of one’s body” (Currie & Ravenscroft 2002, p. 88). So on Currie and Ravenscroft’s suggestion, imagining playing the Waldstein sonata involves re-creating the perception of bodily movements.

Certainly, in order to imagine performing an action, it is not enough to re-create a visual experience of the appropriate bodily movements—otherwise, the relevant type of imagining would belong to sensory imagination after all. Alternatively, one might suggest that motor imagery involves re-creating a proprioceptive experience of the appropriate bodily movements. However, such imagining does not entail re-creating an agentive experience, even if it may accompany the latter. In a similar vein, Goldman claims that motor imagery “is the representation or imagination of executing bodily movement” and has as its counterpart “events of motor production, events occurring in the motor cortex that direct behavior” (Goldman 2006, pp. 157–158). Following Goldman, we can say that imagining playing the Waldstein sonata may involve re-creating an execution of the appropriate bodily movements.

In fact, an ordinary case of imagining playing the Waldstein will probably involve (at least) three types of imagining:

Imagining seeing movements of one’s fingers on the keyboard.

Imagining having a proprioceptive experience of these movements.

The three types of imagining are typically entangled within a single imaginative endeavor. That is, someone who imagines playing the sonata will typically imagine having a proprioceptive experience of her fingers running on the keyboard but also various sensory experiences: visual experiences of her moving fingers and auditory experiences of the music. Still, each type is essentially distinct from the others, and might even be dissociable in special circumstances (although we do not want to insist too much on the possibility of such dissociation). Suppose for instance that one imagines one’s limbs being remotely controlled. One can imagine from a proprioceptive perspective one’s arms and legs going through the motions characteristic of playing the piano without imagining oneself playing the piano. In this case, (ii) is instantiated but (iii) is not. More controversially, suppose that one imagines oneself being selectively anesthetized, or in the situation of a deafferented subject.[7] Perhaps one can then imagine playing the piano without imagining having a proprioceptive experience; (iii) but not (ii) would be instantiated. Given the role of proprioceptive feedback in the ordinary execution of action, it is probably hard if not impossible to imagine playing a whole sonata in the absence of any proprioceptive-like imagining, but the relevant dissociation is in principle possible for simpler actions, such as stretching one’s finger. Finally, it seems possible to imagine playing the piano without re-creating any visual or auditory experience. For instance, one can imagine playing the sonata with one’s eyes closed or one’s ears blocked. Here, (iii) is instantiated but (i) is not. Again, given the role of sensory feedback in the ordinary execution of action, it might be hard to form such a selective imagining, especially if the action gets complicated.

The upshot of the foregoing discussion is that only (iii) is a genuine case of motor imagery. It involves the re-creation of what philosophers of action call the “sense of agency” or the “sense of control” (see e.g., Haggard 2005 and Pacherie 2007). Since the sense of agency or control is a conscious experience, motor imagery clearly falls under the umbrella of experiential imagination. Moreover, to the extent that motor imagery is (at least in principle) dissociable from sensory imagination, even if it typically depends on the latter, it is a case of non-sensory imagination.[8]

What about (ii)? Proprioception is arguably a mode of perception; it is a way of perceiving the spatial disposition of one’s body.[9] In this respect, (ii) is like (i), which is a case of sensory imagination. However, proprioception is also essentially or at least normally a way of gaining information about oneself; what proprioception is about is a bodily state of oneself. In this respect, (ii) is more like (iii), which also involves a way of gaining information about oneself, and more precisely one’s actions.[10]

What unifies (ii) and (iii) as cases of non-sensory imagination is the fact that what is re-created is a (non-imaginative) internal experience. An internal experience is essentially or at least normally de se, in the following sense: it is supposed to be about a mental or bodily state of oneself. Proprioceptive and agentive experiences are both internal in this sense. At least in normal circumstances, one cannot have a proprioceptive experience of another’s body or a sense of agency for another’s action. In contrast, all cases of sensory imagination are such that what is re-created is a (non-imaginative) external experience. An external experience is typically about the external world and is only accidentally de se. For instance, vision is an external experience; it is a way of gaining information about one’s immediate surroundings, whether or not one also sees oneself.[11]

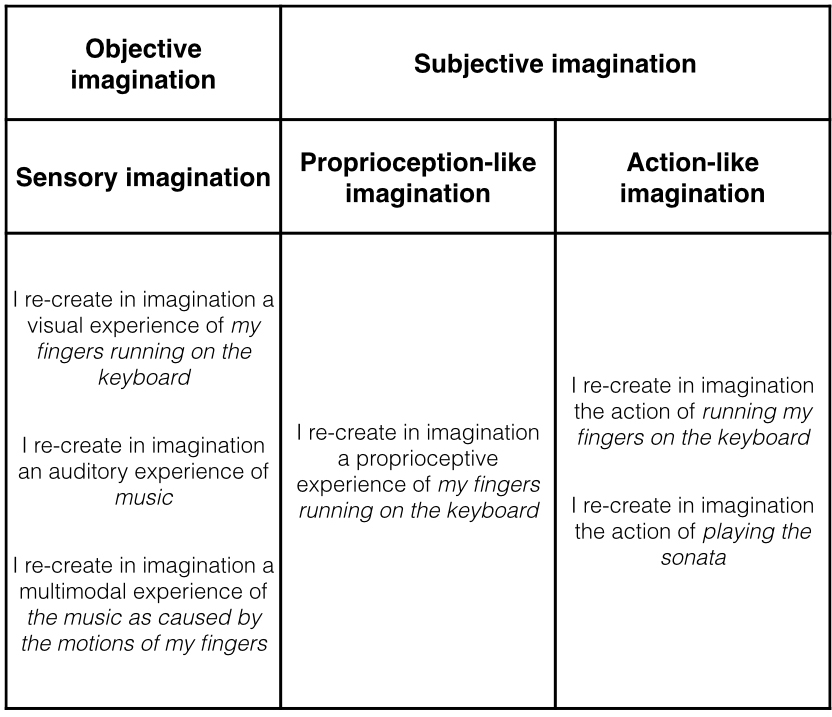

These considerations allow us to give a more fine-grained analysis of the realm of experiential imagination based on the external versusinternal contrast, rather than the sensory versus non-sensory contrast. In a nutshell, we can say that experiential imagination comes in two varieties. Experiential imagination can re-create: (a) some external experience—e.g., a way of gaining information about the world (e.g., I imagine seeing Superman flying in the air), and (b) some internal experience—e.g., a way of gaining information about oneself (e.g., I imagine having a proprioceptive experience of flying in the air). Following Jérôme Dokic (2008), we shall call (a) “objective imagination” and (b) “subjective imagination”; see figure 1.[12]

Figure 1: Types of imagining involved in playing a sonata

Figure 1: Types of imagining involved in playing a sonata

We may thus introduce two other hypotheses subordinate to GH, which we call the Objective Hypothesis (ObjH) and the Subjective Hypothesis (SubjH):

ObjH =Df To imagine something objectively is always at least to re-create some external experience.

SubjH =Df To imagine something subjectively is always at least to re-create some internal experience.

Sensory imagination forms an important sub-class of experiential imagination, but it can also be seen as a paradigmatic case of objective imagination, since it involves re-creating an external experience. Experiential imagination is not merely objective imagination, since another sub-class of experiential imagination, namely subjective imagination, is constituted by cases in which an internal experience is re-created. For instance, imagining having one’s legs crossed or driving a Ferrari may involve re-creating some internal non-sensory experience, namely a proprioceptive and/or agentive experience as of having one’s legs crossed or driving a Ferrari.

To sum up, we have identified two important varieties of imagination that seem to exhaust the domain of experiential imagination: objective and subjective imagination.[13] We have argued that this distinction, which gives rise to phenomenologically different imaginings, traces back to an independent distinction within the domain of non-imaginative experiences, between external and internal experiences. We have also claimed that sensory imagination, which is the variety of experiential imagination most commonly recognized, should be seen as a paradigmatic example of objective imagination. More should be said about the distinction between objective and subjective imagination. For instance, questions arise as to whether sensory imagination exhausts the field of objective imagination and as to whether subjective imagination encompasses more than proprioceptive or agentive experiences.

The remainder of the paper is devoted to further clarification of the notions of objective and subjective imagination. We shall begin with a comparison between our own proposal and Zeno Vendler’s observations about imagination.