4 Vendler’s varieties of imagination

A well-informed reader might think that our distinction between objective and subjective imagination is the same as a homonymous distinction introduced by Vendler (1984). Certainly Vendler intends to capture two phenomenologically different ways of imagining, which potentially correspond to our distinction between external and internal experiential perspectives (perspectives on the world and perspectives on oneself). However, he also gives a prima facie interpretation of the distinction between objective and subjective imagination, which has more to do with the way the self is involved in our imaginings than with the distinction between external and internal experiences. On this interpretation, Vendler’s notions of objective and subjective imagination arguably diverge from ours. Let us start with Vendler’s interpretation of these notions (section 4.1) and then move to a deeper analysis of the contrast examples offered by Vendler in order to motivate his distinction (section 4.2). In so doing, we shall show that our construction of the objective versus subjective distinction is more helpful in order to map the realm of experiential imagination.

4.1 Two kinds of self-involvement

Vendler (1984) suggests that the phrase “S imagines doing A” invites what he calls “subjective” imagination, while the phrase “S imagines herself/himself doing A” can be used to describe “objective” imagination. Prima facie, Vendler seems to interpret the distinction between subjective and objective imagination in terms of two ways in which the self can be involved in our imaginings—implicitly or explicitly.

Subjective imagination concerns cases in which the self is implicitly involved in the imagining, whereas objective imagination concerns cases in which the self is explicitly involved in the imagining. This is why the phrase “imagining doing A”, which does not explicitly mention the agent of the action A, is best used to describe subjective imagination, whereas the phrase “imagining myself doing A”, which explicitly mentions myself as the agent of the action A, is more suitable to the description of objective imagination.

The self is implicitly involved in an imagining when it fixes the point of view internal to the imagined scene without being a constituent of that scene. One can imagine seeing the Panthéon from the other end of rue Soufflot without imagining oneself as another object in the scene. Still, the scene is imagined from a specific point of view, as defined by a virtual self. One can also imagine seeing oneself in front of the Panthéon. In such a case, the self is a constituent of the imagined scene—it is explicitly represented as a part of the imagining’s content.

Of course, when one imagines seeing oneself in front of the Panthéon, one’s imagining also involves the self implicitly. One imagines a scene from the perspective of a virtual self, which is distinct from oneself as a constituent of the scene. As a consequence, Vendler makes clear that subjective and objective imagination are not mutually exclusive. Commenting on Vendler’s distinction, François Recanati concurs, writing that “the objective imagination is a particular case of the subjective” (Recanati 2007, p. 196).

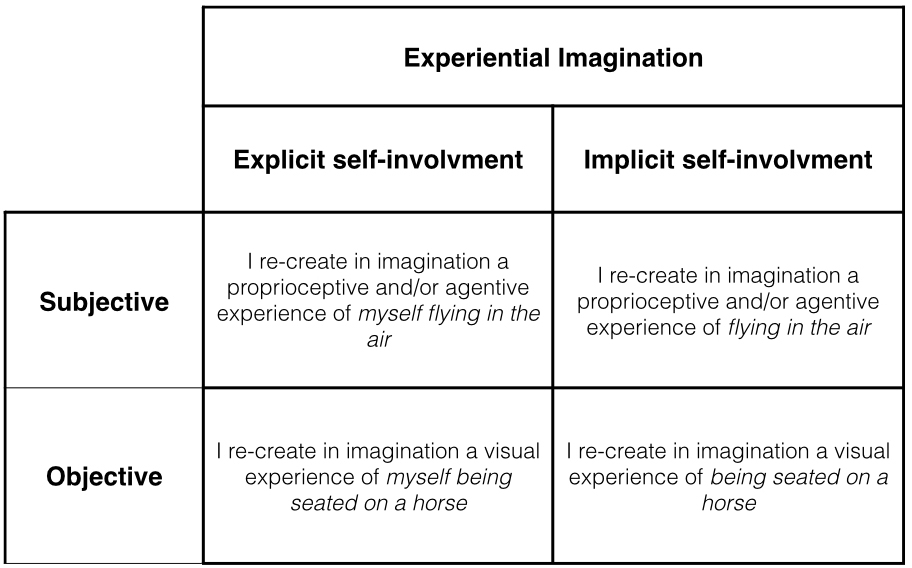

It should be sufficiently apparent that the distinction between implicit and explicit self-involvement is a matter of the imagining’s content and more precisely deals with the issue of how the self is involved in imagination. In contrast, the distinction between internal and external experiential perspectives has to do with the mode re-created in imagination, respectively an external and an internal experience. Therefore, the two distinctions answer different questions and turn out to be orthogonal.

First, objective imagination can involve the self either implicitly or explicitly (but not both at the same time). This is easily seen by considering the Panthéon example. Peacocke himself suggests another relevant case. He observes that the phrase “imagining being seated on a horse” is ambiguous between adopting the point of view of the rider (namely oneself) and adopting the point of view of someone else who could see the rider (see Peacocke 1985, p. 23). If the relevant perspective is that of the rider (namely oneself), the self need not be a constituent of the imagined scene—in this case (where the rider does not see any part of her body), it is implicitly involved in the imagining. In contrast, if the relevant perspective embraces oneself as the rider, the self is explicitly involved; it figures in the content of the imagining. However, both interpretations involve visual (i.e., external) perspectives, so what is at stake is a distinction within objective imagination rather than a contrast between subjective and objective imagination.[14]

Second, it is at least arguable that subjective imagination can involve the self either implicitly or explicitly. Suppose that one subjectively imagines swimming in the ocean. One may re-create the internal experience of what Marc Jeannerod & Elisabeth Pacherie (2004) call a “naked” intention (in action), which precisely does not involve an explicit representation of the agent. In this case, no self is part of the representational content of one’s imagining. One subjectively imagines swimming without imagining the agent as such, whether oneself or anyone else. However, one might also re-create a more complex internal experience, whose content embraces oneself as the agent of the action of swimming. Accordingly, in this case, the self (oneself) is explicitly represented in the content of one’s subjective imagining. One subjectively imagines a particular agent swimming; in Vendler’s example, that particular agent is oneself.

One might object to the last point and claim that the self is never an object of internal experience. One can have at best internal experiences of particular mental states, such as intentions in action, but never of oneself having those mental states. However, this is a substantial claim that certainly needs to be backed up by careful arguments. Note that the assumption that the self can figure in the content of an internal experience is in principle compatible with the Humean point that the self cannot be introspected. Introspection, conceived as a form of inner perception, is only one type of internal experience. Perhaps there are non-introspective cases of internal experience whose explicit contents cannot be fully specified except by using the first-person pronoun. For instance, one might argue that at least some cases of proprioception as well as internal experiences of controlling one’s body as a whole give us access to one’s self, or at least to the boundaries between oneself and the rest of the environment.[15]

Consider other examples offered by Vendler. When you imagine yourself eating a lemon by imagining your pinched face, your imagining is explicitly self-involving and might be fulfilled via objective imagination, such as visual imagination, but also via subjective imagination, such as proprioceptive imagination, at least to the extent that it recreates an internal experience of your bodily self. What about imagining implicitly involving the self? If while imagining eating a lemon, the subject imagines the action of eating a lemon and nothing else, she is exploiting her subjective imagination, insofar as she is re-creating an agentive perspective. It seems possible to imagine eating a lemon via objective imagination too, for instance by re-creating a visual experience as of an action independently of any identification of the agent.

To sum up, while the distinction between subjective and objective imagination seems to capture two forms or modalities of imagination, the distinction between two kinds of self-involvement, although important in itself, is less relevant to a taxonomy of experiential imagination. The orthogonality of these distinctions is shown again in figure 2. In the following sub-section we shall further motivate our hypothesis that Vendler’s own contrast examples are best understood in terms of the independently motivated distinction between internal and external experiences.

Figure 2: Explicit and implicit self-involvement in subjective and objective imagination

Figure 2: Explicit and implicit self-involvement in subjective and objective imagination

4.2 Vendler’s examples revisited

Aside from his interpretation of subjective imagination as implicitly self-involving and objective imagination as explicitly self-involving, Vendler clearly draws our attention to two ways of imagining a given action, which have quite different phenomenological profiles. In his own words:

We are looking down upon the ocean from a cliff. The water is rough and cold, yet there are some swimmers riding the waves. ‘Just imagine swimming in that water’ says my friend, and I know what to do. ‘Brr!’, I say as I imagine the cold, the salty taste, the tug of the current, and so forth. Had he said ‘Just imagine yourself swimming in that water’, I could comply in another way, too: by picturing myself being tossed about, a scrawny body bobbing up and down in the foamy waste. (Vendler 1984, p. 43)

As some of Vendler’s other examples show, the relevant distinction is not restricted to imagining actions:

In order to familiarize yourselves with this distinction, imagine eating a lemon (sour taste), and then imagine yourself eating a lemon (pinched face); imagine being on the rack (agony), and then yourself being on the rack (distorted limbs); imagine whistling in the dark (sensation of puckered lips), and then yourself whistling in the dark (distance uncertain, but coming closer); and so forth. (Vendler 1984, p. 43)

It is not immediately clear what is common to all cases of subjective or objective imagination in Vendler’s examples. Consider the suggestion that the relevant distinction can be explained at the level of the states represented by the imaginings. Subjective imagination would involve imagining states that cannot be imagined objectively. For instance, in imagining swimming in the water, I also imagine proprioceptive experiences, which (one might argue) cannot be imagined objectively. How could we visually imagine such experiences, which are essentially felt?

However, it is not obvious that the essence of the distinction between subjective and objective imagination can be fully captured by reference to the imagined states. One can imagine having one’s legs crossed via subjective imagination, but also via objective imagination. The first type of imagining is akin to proprioception (one imagines feeling one’s legs crossed), while the second type of imagining is akin to vision (one visualizes oneself with one’s legs crossed). Yet these imaginings are about the same bodily condition—having one’s legs crossed.

Similarly, the very same action of swimming in the ocean can be imagined subjectively or objectively. The case of pain is more controversial, but if one can be visually aware that someone is in pain (by observing pain-related behavior), then one can imagine the very same pain state either subjectively or objectively. The difference between the relevant imaginings must lie elsewhere.

We are now in the position to see that we were on the right track and that Vendler’s contrast examples are plausibly construed as involving different experiential perspectives on a given scene, either internal (perspectives on oneself) or external (perspectives on the world). Subjective imagination has to do with the former, and objective imagination with the latter. This is easily seen by considering the example of imagining whistling in the dark. Vendler contrasts the subjective case, in which the subject imagines the sensation of puckered lips, with the objective case, in which the subject imagines the distance uncertain, but coming closer. In other words, what Vendler seems to contrast is proprioception-like imagination with auditory imagination or, in our terminology, an internal experiential perspective with an external one.

More generally, Vendler seems to be concerned with the difference between, on the one hand, imagining doing an action (e.g., swimming, eating, whistling, etc.) or having pain (e.g., agony), where what the imaginer re-creates is the relevant experience and, on the other hand, imagining pieces of behaviour that reveal the very same experience (e.g., visualizing an eating mouth or a body in agony), where what the imaginer re-creates is an external perspective on the relevant experience.[16]

Let us note that, in order to make his contrast more realistic, Vendler gives us complex examples, where more than one experience is involved. So for instance, his example of imagining swimming in the ocean clearly belongs to subjective imagination, since the re-creation of a proprioceptive and/or agentive experience is involved. As Vendler suggests, though, when you fulfill this imagining you can also re-create various external experiences, such as “the cold, the salty taste, the tug of the current, and so forth”. The same is true in the case of imagining eating a lemon. When you imagine eating a lemon, you re-create in imagination an internal experience (e.g., the proprioceptive and/or agentive experience of eating), but your imagining can be accompanied by others that re-create external experiences (e.g., the sour taste, the yellow lemon).

The discussion of Vendler’s distinction has led us to strengthen our taxonomy of experiential imagination. So far we have seen that, first, all cases covered by SenH seem to be cases of objective imagination (and thus covered by ObjH), which involves re-creating some external experience. Second, all cases covered by SubjH arguably involve re-creating some internal experience.

However, another important type of imagination emerges from the literature on imagination, namely cognitive imagination, which has been defined as belief-like and typically contrasted with sensory or even experiential imagination.