4 Bayesian expectations

Here is where Bayesian expectations (see Clark 2013) could play an iterated role: our ontology (in the elevator sense) does a close-to-optimal job of representing the things in the world that matter to the behavior our brains have to control (cf. Metzinger 2003, on our world models). Hierarchical Bayesian predictions accomplish this, generating affordances galore: we expect solid objects to have backs that will come into view as we walk around them, doors to open, stairs to afford climbing, cups to hold liquid, etc. But among the things in our Umwelt that matter to our wellbeing are ourselves! We ought to have good Bayesian expectations about what we will do next, what we will think next, and what we will expect next! And we do. Here's an example:

Think of the cuteness of babies. It is not, of course, an “intrinsic” property of babies, though it seems to be. What you “project” out onto the baby is in fact your manifold of “felt” dispositions to cuddle, protect, nurture, kiss, coo over, … that little cutie-pie. It's not just that when your cuteness detector (based on facial proportions, etc.) fires, you have urges to nurture and protect; you expect to have those very urges, and that manifold of expectations just is the “projection” onto the baby of the property of cuteness. When we expect to see a baby in the crib, we also expect to “find it cute”—that is, we expect to expect to feel the urge to cuddle it and so forth. When our expectations are fulfilled, the absence of prediction error signals is interpreted as confirmation that, indeed, the thing in the world with which we are interacting has the properties we expected it to have. Without the iterated expectations, cuteness could do its work “subliminally,” outside our notice; it could be part of our “elevator ontology” (the ontology that theorists need to posit to account for our various dispositions and talents) but not part of our ontology, the things and properties we can ostend, reflect on, report, discuss, or appeal to when explaining our own behavior (to ourselves or others). Cuteness as a property passes the Bayesian test for being an objective structural part of the world we live in (our manifest manifest image), and that is all that needs to happen. Any further “projection” process would be redundant. What it is to experience a baby as cute is to generate the series of expectations and confirmations just described. What is special about properties like sweetness and cuteness is that their perception depends on particularities of the nervous systems that have evolved to make much of them. The same is of course also true of colors. This is what is left of Locke’s (and Boyle’s) distinction between primary and secondary qualities.[1]

Similarly, when we feel the urge to judge something about “that red stripe” (in the American flag afterimage (see Figure 1) that hovers in our visual field, we have the temptation to insist that there is a red stripe—there has to be!—causing us to seem to see it. But however natural and human this temptation is, it must be resisted. We can be caused to seem to see something by something that shares no features with the illusory object. (Remember Ebenezer Scrooge saying to Marley’s ghost: “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There's more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!” Many would insist that there has to be a ghost-shaped intermediary in the causal chain between blot of mustard and belief in Marley, but Scrooge might be right in addressing his remark to the cause of his current condition, and be leaving nothing Marley-shaped out.) And as for the idea that without being rendered such contents are causally impotent, it is simply mistaken, as a thought experiment will reveal. Suppose we have a drone aircraft hunting for targets to shoot at, and suppose that the drone is equipped with a safety device that is constantly on the lookout for red crosses on buildings or vehicles—we don’t want it shooting at ambulances or field hospitals! With its video eye it takes in and transduces (into digital bit streams) thirty frames a second (let’s suppose) and scans each frame for a red cross (among other things). Does it have to project the frame onto a screen, transducing bit streams into colored pixels? Of course not. It can make judgments based on un-transduced information—in fact, it can’t make judgments based on anything else. Similarly your brain can make judgments to the effect that there is a red stripe out there on the basis of spike train patterns in your cortex, and then act on that judgment (by causing the subject to declare “I seem to see a red stripe,” or by adjusting an internal inventory of things in the neighborhood, or …). (I am deliberately using the word “judgment” for the drone’s discriminations and the brain’s discriminations; I have elsewhere called such items micro-takings or content-fixations. The main point of using “judgment” is to drive home the claim that these events are not anything like the exemplification of properties, intrinsic or otherwise. They are not qualia, in other words. Qualia—as typically conceived—would only get in the way. Don’t put a weighty LED pixel screen in a drone if you want it to detect red crosses, and don’t bother installing qualia in a brain if you want it to have color vision. Whatever they are, qualia are unnecessary and may be jettisoned without loss.)

So the familiar idea (familiar in the context of Block’s proposed distinction between access consciousness and phenomenal consciousness) that phenomenal consciousness (= qualia) is the basis for access consciousness (= judgments about qualia, qualia-guided decisions, etc.) is backwards.[2] Once the discerning has happened in the untransduced world of spike trains, it can yield a sort of Humean projection—of a red stripe or red cross or just red, for instance—into “subjective space.”

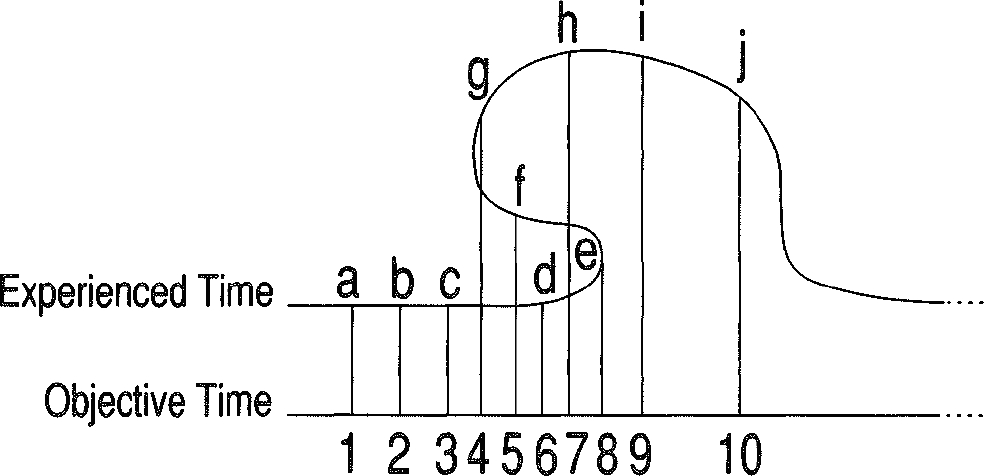

But what is this subjective space in which the projection happens? Nothing. It is a theorist’s fiction. The phenomenon of “color phi” nicely illustrates the point. When shown, say, two disks displaced somewhat from each other, one sees the apparent motion of a single disk—the phi phenomenon that is the basis of animation (and motion pictures in general). If the disks are of different colors—the left disk red and the right disk green, for instance—one will see the red disk moving rightward and changing its color to green in mid-trajectory. How did the brain “know” to move the disk rightward and switch colors before having access to the green disk at its location? It couldn’t (supposing precognition to be ruled out). But it could have Bayesian expectations of continuous motion from place to place that provoke a (retrospective) expectation of the intermediate content, and this expectation encounters no disconfirmation (if the timing is right), which suffices to establish in reality the illusory sequence in the subject’s manifest image. So the visual system’s access to the information about the green disk is causally prior to the “phenomenal” motion and color change. Here is a diagram of color phi from Consciousness Explained (and Dennett & Kinsbourne 1992):

Figure 2: Superimposition of subjective and objective sequences.

Figure 2: Superimposition of subjective and objective sequences.

In order to explain “temporal anomalies” of conscious experience, we need to appreciate that not only do we not have to represent red with something red, and round with something round; we don’t have to represent time with time. Recall my example “Tom arrived at the party after Bill did.” When you hear the sentence you learn of Tom’s arrival before you learn of Bill’s, but what you learn is that Bill arrived earlier. No revolution in physics or metaphysics is needed to account for this simple distinction between the temporal properties of a representation and the temporal properties represented thereby. It is quite possible (in color phi, for instance) for the brain to discern (in objective time) first one red circle (cat time 3) and then a green circle (fat time 5) displaced to the right, and then to (mis-)represent an intermediate red-turning-green circle (eat time 8) yielding the subjective judgment of apparent motion with temporally intermediate color change. Here our Bayesian probabilistic anticipator is caught in the act, jumping to the most likely conclusion in the absence of any evidence. Experienced or subjective time doesn’t line up with objective time, and it doesn’t have to. The important point to remember from the diagram is that the subjective time sequence is NOT like a bit of kinked film that then has to be run through a projector somewhere so that c is followed by e is followed by f in real time. It is just a theorist’s diagram of how subjective time can relate to objective time. Subjective time is not a further real component of the causal picture. No rendering is necessary, the judgment is already in, and doesn’t have to be re-presented for another act of judging (in the Cartesian Theater).

The temptation to think otherwise may run deep, but it is fairly readily exposed. Consider fiction. Sherlock Holmes and Watson seem real when one is reading a Conan Doyle mystery—as real as Disraeli or Churchill in a biography. When Sherlock seems real, does this require him and his world to be rendered somewhere, in—let’s call it—fictoplasm? No. There is no need for a medium of fictoplasm to render fiction effective, and there is no need for a mysterious medium, material or immaterial, to render subjective experience effective. No doubt the temptation to posit the existence of fictoplasm derives from our human habit, when reading, of adding details in imagination that aren’t strictly in the book. Then, for instance, when we see a film of the novel, we can truly say “That’s not how I imagined Holmes when I read the book.”

Isn’t such rendering in imagination while reading a novel a case of transduction of content from one medium (written words as seen on the page) into another (imagined events as seen and heard in the mind’s eye and ear)? No, this is not transduction; it is, more properly, a variety of translation, effortlessly expanding the content thanks to the built-in Bayesian prediction mechanisms. We could construct, for instance, a digital device that takes problems in plane geometry presented in writing (“From Euclidean axioms prove the Pythagorean Theorem.”) and solves them through a process that involves making Euclidean constructions, with all the sides and angles properly represented and labeled, and utilizing them in the proof. The whole process from receipt of the problem to delivery of the called-for proof (complete with printed-out diagrams if you like), is conducted in a single medium of digital bit strings, with no transduction until the printer or screen is turned on to render the answer. (A more detailed description of this kind of transformative process without transduction is found in my discussion (1991) of how the robot Shakey discriminated boxes from pyramids.)

Consider Figure 2 above. Does the access/phenomenal consciousness distinction get depicted therein? If so, access consciousness should be identified with the objective time line, and phenomenal consciousness (if it were something real in addition to access consciousness) would be depicted in the line that doubles back in time. The content feature that creates the kink is an effect of a judgment or discernment that came later in objective time than the discernment of the green circle at time 5. It is because the brain already had access to red circle, then green circle that it generated a representation (but not a rendering) of the in-between red-turning-green circle as an elaborative effect.[3]