3 It still seems that qualia exist

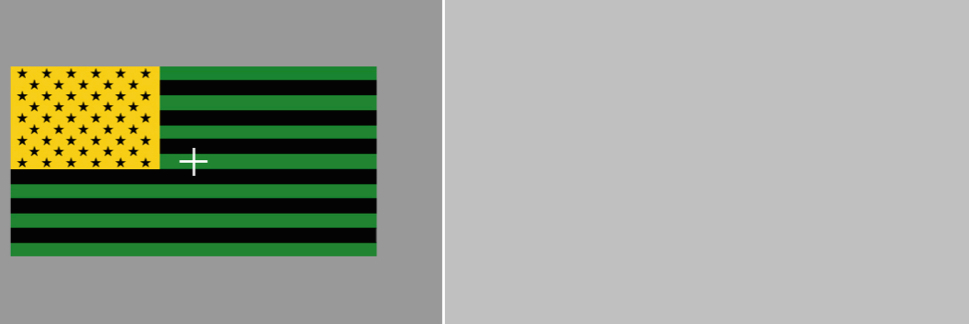

But it sure seems that qualia exist, in spite of the foregoing! How could they not? Aren’t they needed, for instance, to be the source or cause of our judgments about them? If I have a conviction that I’m seeing an American flag afterimage (see figure 1), and note that the lowest short red stripe intersects the central cross, doesn’t there have to be the red stripe I deem myself to be experiencing? Isn’t the presence of that red stripe somewhere a necessary condition for me seeming to see a red stripe? No, and the alternative has been at least dimly understood since Hume’s brilliant discussion of our experience of causation.

Figure 1: Inverted American Flag.

Figure 1: Inverted American Flag.

Consider what I will call Hume’s Strange Inversion (cf. Dennett 2009). We think we see causation because the causation in the world directly causes us to see it—the same way round things in daylight cause us to see round things, and tigers in moonlight cause us to see tigers. When we see the thrown ball causing the window to break, the causation itself is somehow perceptible “out there.” Not so, says Hume (1739, section 7 “Of the idea of necessary connexion”). What causes us to have the idea of causation is not something external but something internal. We have seen many instances of As followed by Bs, Hume asserts, and by a process of roughly Pavlovian conditioning (to put it anachronistically) we have been caused by this series of experiences to have in our minds a disposition, when seeing an A, to expect a B—even before the B shows up. When it does, this felt disposition to expect a B is mis-identified as an external, seen property of causation. We think we experience causation between A and B, when we are actually experiencing our internal judgment “here comes a B” and “projecting” it into the world. This is a special case of the mind’s “great propensity to spread itself on external objects” (Hume 1739, I, xiv). In fact, Hume insisted, what we do is misinterpret an inner “feeling”—an anticipation—as an external property. The “customary transition” in our minds is the source of our sense of causation, a quality of “perceptions, not of objects,” but we mis-attribute it to the objects, a sort of benign user-illusion, to speak anachronistically again. As Hume notes, “the contrary notion is so riveted in the mind” that it is hard to dislodge. It survives to this day in the typically unexamined assumption that all perceptual representations must be flowing inbound from outside.

Hume wrote that the ‘mind has a great propensity to spread itself on external objects’ (T 1.3.14.25; SBN 167) and that we ‘gild and stain’ natural objects ‘with the colours borrowed from internal sentiment’ (EPM Appendix 1.19; SBN 294). These metaphors have invited a further one: that of ‘projection’ and its cognates. Though not Hume’s own, the projection metaphor is now so closely associated with him, both in exegetical and non-exegetical contexts, that the phrase ‘Humean projection’ is something of a cliché in philosophical discourse. (Kail 2007, p. 20)

Here are a few other folk convictions that need Strange Inversions: sweetness is an “intrinsic” property of sugar and honey, which causes us to like them; observed intrinsic sexiness is what causes our lust; it was the funniness out there in the joke that caused us to laugh (Hurley et al. 2011). There is no more familiar and appealing verb than “project” to describe this effect, but of course everybody knows it is only metaphorical; colors aren’t literally projected (as if from a slide projector) out onto the front surfaces of (colorless) objects, any more than the idea of causation is somehow beamed out onto the point of impact between the billiard balls. If we use the shorthand term “projection” here to try to talk, metaphorically, about the mismatch between manifest and scientific image (Sellars 1962), what is the true long story? What is literally going on in the scientific image? A large part of the answer emerges, I propose, from the predictive coding perspective. Every organism, whether a bacterium or a member of Homo sapiens, has a set of things in the world that matter to it and which it (therefore) needs to discriminate and anticipate as best it can. Call this the ontology of the organism, or the organism’s “Umwelt” (von Uexküll 1957). This does not yet have anything to do with consciousness but is rather an “engineering” concept, like the ontology of a bank of elevators in a skyscraper: all the kinds of things and situations the elevators need to distinguish and deal with. An animal’s “Umwelt” consists in the first place of affordances (Gibson 1979), things to eat or mate with, openings to walk through or look out of, holes to hide in, things to stand on, and so forth. We may suppose that the “Umwelt” of a starfish or worm or daisy is more like the ontology of the elevator than like our manifest image. What’s the difference? What makes our manifest image manifest (to us)?