8 Is there a functional boundary between unconscious and conscious vision?

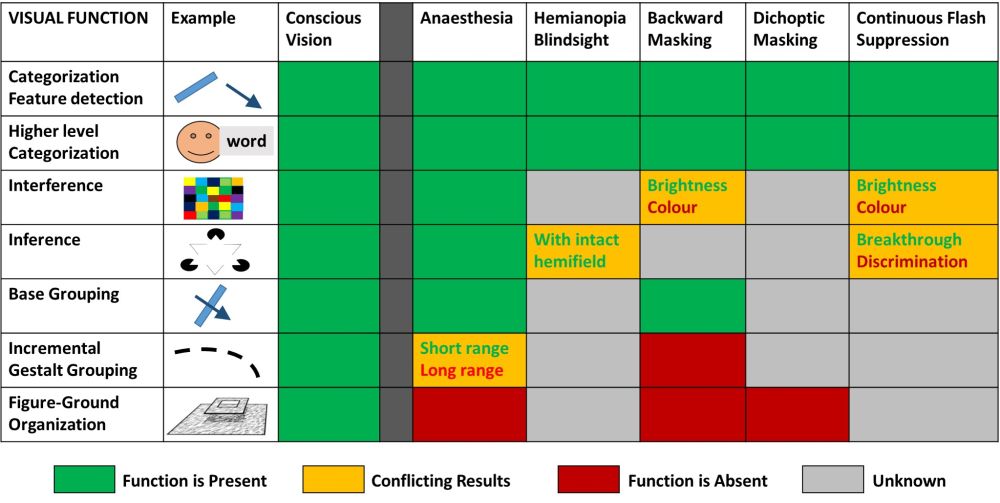

I have taken the two extreme ends of consciousness manipulation: clear-cut visible and above-threshold items in awake subjects veridically reporting their visual experiences versus visual processing in anaesthesia, blindsight, or during profound masking or suppression (figure 11). If we don’t accept conscious vision in the former, and the absence of it in the latter, there is no use arguing about the phenomenon of consciousness. Even so, it has been surprisingly hard to find fundamental differences in the workings of many visual functions in the two conditions. Categorization of visual stimuli, even up to high levels, clearly stands independent of conscious visibility. It is unclear whether interference—i.e., the fact that features are no longer treated independently—depends on consciousness: shifts in brightness perception do not depend on consciousness, while it is uncertain whether the transition from wavelength to colour perception (and colour constancy) marks the conscious-unconscious divide.[28] Similarly, the status of inference phenomena like those observed in the Kanizsa triangle is uncertain.

This is all the more surprising given that many of these functions have traditionally been viewed as expressing the transition from merely physical features detected by sensor arrays towards the perceptual interpretation of this information. Moreover, they mark the integration of stimulus-driven input with our knowledge of the world, such that we arrive at visual “meaning”. Recently, there has been quite some interest in so called predictive coding frameworks of vision (Rao & Ballard 1999; Panichello et al. 2012). In these frameworks, vision is seen as a type of Bayesian inference, where our prediction (prior) of the outside world is continuously matched with our sensory input, and where the difference is propagated through the network as an “error signal”, which then results in an updating of the model (posterior). Indeed, expectations bias our perception of the world, most strongly in the face of ambiguous stimuli, but also in the case of unambiguous stimuli (Panichello et al. 2012). Although it has been suggested that either the matching process, the prior, or the posterior in this type of inference have some relation to consciousness,[29] this is questionable given the automaticity of many expectation effects. For example, the mere statistical dominance of a particular stimulus type is sufficient to bias perceptual interpretations (Chopin & Mamassian 2012). Also, expected words break from continuous flash suppression sooner than unexpected words (Costello et al. 2009).[30]

All in all, the relation between consciousness on the one hand and categorization, interference, and inference processes on the other hand ranges from non-existent to weak. A much stronger case seems possible for functions like the grouping of image elements according to Gestalt laws and figure-ground segregation. These operations seem to depend strongly on the conscious state, and on conscious perception of the stimuli involved (figure 11). This is surprising, given their relative “simplicity”. For example, the grouping of similarly-oriented or collinear line segments may be achieved by horizontal connections in the primary visual cortex (Bosking et al. 1997, see above). Figure–ground segregation—and its neurophysiological correlate—has been successfully modelled in a recurrent network architecture consisting of orientation-selective visual neurons in three hierarchically-organized visual areas, combined with some inhibitory horizontal interactions and excitatory feedback (Roelfsema et al. 2002). Regardless, the experimental data clearly show that if we want to identify visual functions that mark the transition from unconscious processing to conscious vision, grouping according to Gestalt laws (incremental grouping) and figure-ground segregation[31] (or perceptual organization in general) are our best bets.[32]

Figure 11: Table summarizing the influence of consciousness manipulation on various visual functions. Colours indicate whether functions (rows) still operate under aa particular manipulation (columns). In the case of conflicting or uncertain evidence (yellow), the cases or conditions where the function still seems present is written in green; the cases where the function is absent are written in red. All functions are assumed to be present in conscious vision. For each visual function, an icon depicts its most prominent example. See text for explanation.

Figure 11: Table summarizing the influence of consciousness manipulation on various visual functions. Colours indicate whether functions (rows) still operate under aa particular manipulation (columns). In the case of conflicting or uncertain evidence (yellow), the cases or conditions where the function still seems present is written in green; the cases where the function is absent are written in red. All functions are assumed to be present in conscious vision. For each visual function, an icon depicts its most prominent example. See text for explanation.