4 Aesthetic judgments

Color plays a large role in a variety of aesthetic judgments. Red broccoli doesn’t look terribly appealing as a food item, and Hollywood maintains that gentlemen prefer blondes. But to what extent are these judgments malleable with experience? Might the red broccoli start to look more appetizing if one has enough experience eating it? To assess these questions we ran two aesthetic judgment experiments. In one, we measured how appealing different dishes looked, and in another we measured judgments of physical attractiveness of people (figure 5). For the first we used images from a large cook-book with a wide variety of dishes. For the second, since both subjects were heterosexual males, we used pictures of adult women taken from the internet. In both cases we separated the stimuli into high-rated and low-rated groups so that we could assess whether color rotation had a differential effect. And in both cases we ran four trials: an unrotated baseline trial of judgments before beginning the rotation period; an early-rotation trial immediately upon wearing the rotation gear; a late-rotation trial at the end of the adaptation period; and finally a post-rotation trial normal color vision was restored. Subjects scored all stimuli with a 1–10 numerical rating. We used the normal vision early-rotation ratings of each subject both to sort stimuli into subject-specific high-rated and low-rated groups, and to establish a normalization (average and standard deviation) so that we could translate all ratings provided by each subject in terms of σ, meaning that 0 was average, 1 was one standard deviation above average, –1 was one standard deviation below average, and so forth.

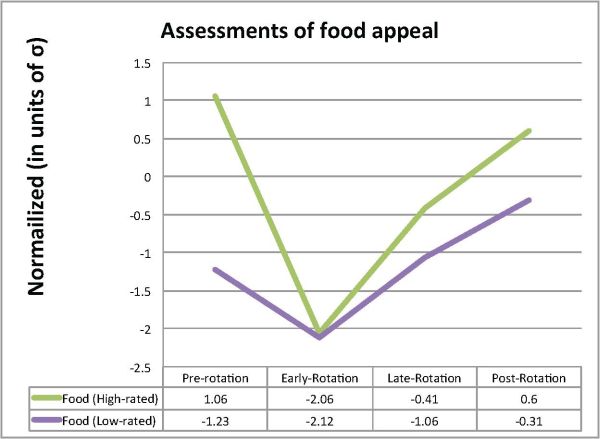

Table 1: Assessments of food appeal. The graphs show the average scores for both subjects. For each subject, before testing each subject scored all images on a scale of 1–10, 10 being the most appealing. These scores were used to establish a normalization for each subject so that all scores could be re-expressed in terms of σ. They were also used to divide the dishes into high-rated and low-rated groups for each subject. Each subject then re-assessed each dish at four times during the experiment: pre-rotation, early-rotation, late-rotation, and post-rotation (see text for explanation). As can be seen, upon color rotation all dishes plummeted in their perceived appeal to a level below the score the unappealing dishes had before rotation. But after adaptation (late rotation) the low-rated dishes regained all of their appeal, and the high-rated ones regained a moderate amount.

The results can be summarized quickly (see table 1). For dishes in the appealing group, their appeal ratings immediately dropped significantly from pre-rotation to early-rotation. The drop was, on average, 3σ, from an average of 1.06σ to an average of –2.06σ! Some notes from JK’s diary speak to the effect of color rotation on food appeal:

Spinach looks a glossy, poisonous red (it's the texture and the color that look really nasty together, I think).

I genuinely lost my appetite at the sight of four enormous bowls of glossy red salad, pale pink cheese, blue kidney beans, deep blue beets, bright red peas, etc. […]

I've noticed that I don't anticipate food at all the way I normally do. Normally during the day I think about food, think about making food, think about eating food, and when I get a full plate of tasty looking food in front of me, I'm a very happy person. Now there's a real disconnect between the way food tastes and the way it looks, and I don't honestly find myself craving anything during the day. I get hungry, yes, but a full plate of food in front of me looks intensely neutral on the desirability scale.

At the end of the adaptation period, those high-rated dishes had regained half of their appeal, being judged on average about –0.41σ. Both RG and JK followed this pattern. Interestingly though, in the post-rotation rating, RG’s ratings returned to within .35σ of baseline for the appealing dishes (to .71σ compared to an initial average rating of 1.06σ), while JK’s ratings were lower, returning only to within 0.61σ of baseline, from 1.09σ to 0.48σ. But this is still a very significant absolute gain. On average, both ratings returned to 0.60σ post-rotation. Again, from JK’s diary after his return to normal vision and going to a salad bar:

The various greens were really intensely "green," the carrots looked like they were going to leap out of the buffet line. The onions (red onions) were the only vegetable that didn't surprise me with its vividness. I was horribly hungry; eating was immensely pleasurable. You have no idea how nice it is for food to look and taste right.

For the less-appealing group of dishes the ratings also dropped immediately from pre-rotation to early-rotation, on average by .89σ, from –1.23σ to –2.12σ. This group of dishes recovered to –1.06σ in late-rotation, just slightly above their pre-rotation ratings. In post-rotation this group of dishes rose to above their baseline ratings, to –0.31σ, nearly a full standard deviation above their pre-rotation baseline!

Interestingly, the overall pattern was that while the high-rated dishes started at 2σ, and low-rated dishes started at –1σ, they all dropped to the same –2σ immediately upon early-rotation. The color rotation just made everything, dishes that normally looked appealing as well as those that did not, look very unappealing. After adaptation at late-rotation, the lower-rated dishes recovered all of their perceived appeal (low though it was), and the higher-rated dishes recovered half. But it is worth remarking that the appealing dishes had a larger absolute gain after adaptation, suggesting that experience with appealing and unappealing food did have an effect on how each subject judged the appeal of foods based on color. Unappealing dishes returned to their normal level of unappeal, and the appealing dishes made significant gains towards looking as appealing as they had before.

As for the physical attractiveness assessments, the effect of color rotation was much less pronounced than it was in the case of food. We dubbed this the Star Trek effect (in honor of Captain Kirk’s romantic liaisons with green alien women): attractive people are still pretty attractive whether their skin is blue, or green, or any other color.

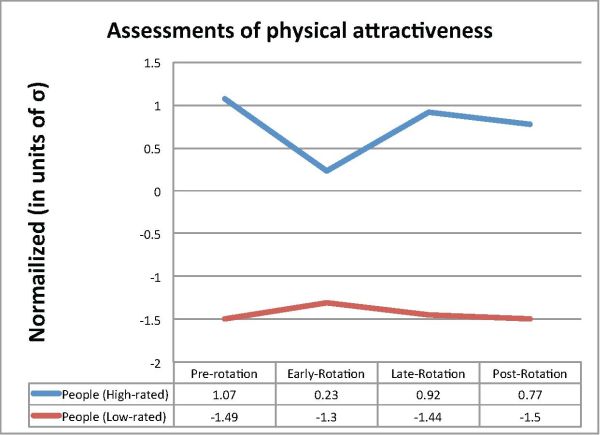

The results are summarized in table 2. As in the case of food, we did an initial norming trial, and then separated stimuli into high-scoring and low-scoring groups. And we tested at the same four times: pre-rotation, early-rotation, late-rotation, and post-rotation. For the low-scoring stimuli, there was almost no difference across the four trials. The average rating in this group started at –1.49σ pre-rotation, and then actually (slightly) improved during early-rotation to –1.30σ. Late-rotation ratings fell to –1.44, and then post-rotation ratings were at –1.50. Basically, color rotation had no pronounced effect on this group, either before or after the adaptation period.

Table 2: Assessments of physical attractiveness of people. The graphs show the average scores for both subjects. For each subject, before testing each subject scored all images on a scale of 1–10, 10 being the most attractive. These scores were used to establish a normalization for each subject so that all scores could be re-expressed in terms of σ. They were also used to divide the images into high-rated and low-rated groups for each subject. Each subject then re-assessed each image at four times during the experiment: pre-rotation, early-rotation, late-rotation, and post-rotation (see text for explanation). As can be seen, color rotation had much less effect on ratings of physical attractiveness of people than it did on the appeal of food. The low-rated group was essentially unchanged throughout the protocol. The high-rated group experienced a relatively small drop during early-rotation, but regained nearly all of it by late rotation.

For the high-scoring stimuli the pattern was more interesting. Pre-rotation average was 1.07σ, which dropped to 0.23σ immediately at early-rotation. While this is indeed a drop, it is a much smaller drop than the corresponding condition with food, in which high-rated dishes dropped 3.00σ. High-rated people ratings dropped only about ¼ as much as high-rated food ratings upon rotation. Late-rotation the high-scoring people had nearly completely rebounded to 0.92σ, only 0.15σ less than their pre-rotation scores. Post-rotation the ratings dropped slightly to 0.77σ, meaning that the people were actually judged to be less attractive in their normal color, than they were when color-rotated, though the degree of drop was small.

The difference we found between food and people is consistent with studies involving less extreme color manipulation. It is well known that color has a very large effect on the appeal of food (Delwiche 2004; Zampini et al. 2007; Shankar et al. 2010). Existing studies of food-color effects typically involve less extreme color manipulations than we studied here, but the results are similar. With people, though skin color does have an effect on perceived attractiveness, structural features (e.g., facial bone structure, symmetry, body proportions) seem to be more significant (Barber 1995; Dixson et al. 2007).