2 The human enhancement debate

In a paper on the “biopolitics” of cognitive enhancement, Peter Reiner recently referred to Plato’s Phaedros, where Socrates discusses what we nowadays might call the psychological side-effects of writing, namely the risk that our memory skills will deteriorate when we rely more on written texts (2013). Interestingly, Socrates’s concerns—voiced some 2400 years ago—seem to be confirmed by recent experiments indicating that people are less likely to remember information when they expect it to be easily accessible with the aid of computers (Sparrow et al. 2011). It goes without saying that everything we do has some psychological or neural impact, whether transient or permanent. However, writing—and, more recently, digital information processing—can be seen as an enhancement technology, as it enables asynchronous and distant communication with contemporaries as well as saving thoughts and ideas for the future.

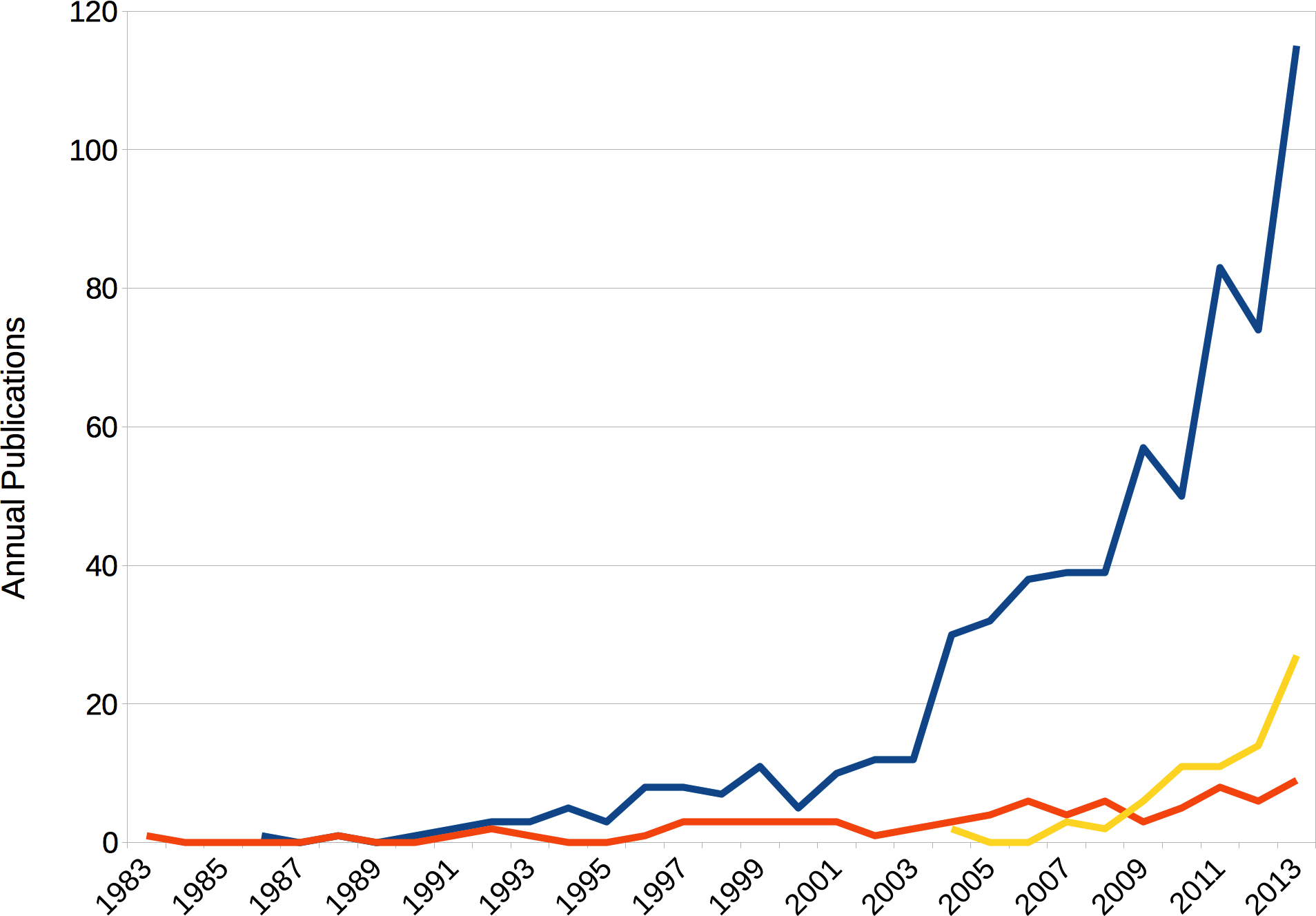

We should keep in mind, though, that the very notion of cognitive enhancement was introduced only recently into the scholarly debate and its increasing prevalence coincided with the institutionalisation of neuroethics in the early 2000s (Figure 1). In the meantime, some authors criticised the exaggerated promises of the debate, pointing out misperceptions in the assessment of pharmacological enhancement behaviour, the complexity of the brain’s neurotransmitter systems, and the insufficient success of the much larger bio-psychiatric paradigm of improving psychological functioning in those looking for treatment (Lucke et al. 2011; Quednow 2010; Schleim 2014a). The latter means that even when the aims of the intervention are clearly circumscribed—e.g., decreasing the severity of the symptoms characteristic of a disorder—and research funds are abundant, bio-psychiatric research has unfortunately not been as successful as expected. This may relativise the hopes for effective bio-psychological enhancement in the healthy in the near future.

Figure 1: Publications on enhancement. Publication data from the ISI Web of Science show a steep increase in publications covering “cognitive enhancement” (blue) that coincides with the institutionalisation of neuroethics (Farah 2012). “Mood” or “affective enhancement” (orange) and “neuroenhancement” (yellow) are addressed much less frequently, although these topics also are increasingly discussed. (ISI Web of Science Topic Search)

Figure 1: Publications on enhancement. Publication data from the ISI Web of Science show a steep increase in publications covering “cognitive enhancement” (blue) that coincides with the institutionalisation of neuroethics (Farah 2012). “Mood” or “affective enhancement” (orange) and “neuroenhancement” (yellow) are addressed much less frequently, although these topics also are increasingly discussed. (ISI Web of Science Topic Search)

While describing writing as a means of cognitive enhancement may seem plausible at first glance, it also carries the risk of neglecting several distinctions that may be ethically and socially important. Such distinctions are, for example, those between learning the use of an instrument to achieve a certain aim and oneself becoming an instrument for the aims of others; between using an external device and directly interfering in the body; and between defining ends autonomously and being adapted to another’s ends heteronomously. Distinctions in actual cases will not always be clear and often fall into a grey zone, but this does not mean that possible interventions cannot be discussed against these concepts. These may be understood as marking the ends of a spectrum: for example, from full autonomy to full heteronomy. Indeed, while some scholars frame the consumption of stimulus drugs such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, or modafinil by students as individual choices for better cognitive functioning (Greely et al. 2008), that is, in an autonomous fashion, several results suggest that students might rather respond to the demands of a competitive academic environment, and thus heteronomously. I will argue later that this opposition between freedom and coercion is the crucible of ethically assessing epigenetic proactivism.

There is already empirical evidence from representative surveys or interviews with students that emphasises the relevance of this distinction. For example, M. Elizabeth Smith & Martha Farah describe in their extensive review on “smart pills” that the largest nationwide study identified admissions criteria (competitiveness) as well as two other social factors as the strongest predictors of stimulant drug consumption (2011). Interviews with non-medical consumers of stimulant drugs at an “elite” college carried out by Scott Vrecko suggest that people use stimulants for emotional and motivational ends rather than for cognitive enhancement, in particular to increase motivation to begin with or to complete boring tasks (2013). Finally, reviewing forty studies on public attitudes toward pharmacological cognitive enhancement, Kimberly J. Schelle and colleagues found that coercion to use drugs is a consistently mentioned concern (Schelle et al. 2014). This evidence associates the availability of enhancements like stimulant drugs with the pressure to adapt people to given standards of performance. Yet in the scientific literature the notion of cognitive enhancement is much more prevalent than the emotional and motivational aspects frequently mentioned in practical contexts (Figure 1).

Scientists and policy-makers in the UK Foresight Project on Mental Capital and Wellbeing note that globalisation increases demands for competitiveness as well as the pressures in our working lives (Beddington et al. 2008; Foresight Project 2008). They conclude that in a rapidly changing world like ours, we must make the most of all our resources in order to keep up with competitors; whole countries have to capitalise on their citizens’ cognitive resources. To achieve this aim, John Beddington and colleagues see vast possibilities in improving a country’s “mental capital” for all members of the population. They identify the possibility to do so at each stage in life, such as the early identification and treatment of people with learning difficulties or the governmental support of those who want to work longer—though, notably, not shorter. A failure to react in a timely way to the challenges would come at a high cost for society, while early intervention in education could improve productivity at work and avoid costs related to a loss of mental capital (Beddington et al. 2008).

This view on performance enhancement for individual and social welfare reflects the focus of influential papers in neuroethics, emphasising the potential improvement of attention, memory, or wakefulness through the consumption of stimulant drugs or other pharmacological substances and neuroscientific technologies affecting the nervous system (Farah et al. 2004; Greely et al. 2008). Assumptions regarding the possible benefits of such substances are frequently based on trials employing test designs from clinical psychology, developed to identify and trace impairment in psycho-behavioural functioning, whether the investigated sample consists of patient populations, healthy people, or both (Bagot & Kaminer 2014; Repantis et al. 2010; Smith & Farah 2011).

Even if such test designs are of high clinical value, it is much less clear what statistically significant, yet often subtle, improvements in such experimental tasks, for example, in planning or memory games, mean for the living environment of the healthy. Whether such improvements indeed translate into an increase in individual wellbeing or the mental capital of a nation has yet to be shown. Indeed it is not even clear what a reliable and ecologically valid way of answering this question would look like. While this is still quite challenging after much debate on pharmacological enhancement, it is presently even less clear what such a standard could look like for epigenetic proactivism. In addition to measuring the benefits, neuroscientists frequently address the possibility of a psycho-behavioural trade-off—that is, the risk that an improvement in one domain would come at a loss in others (Brem et al. 2014; Hills & Hertwig 2011; Quednow 2010; Wood 2014). Given these complexities in the empirical research on enhancement, it will be helpful to introduce an explicit definition for further discussion.

Human Enhancement =Df A change in the biology or psychology of a person which increases the chances of leading a good life in the relevant set of circumstances.

Notice how this definition, proposed by Julian Savulescu and colleagues in the introduction to a recent edited volume on human enhancement (Savulescu et al. 2011), relates the good life of an individual—its biology or psychology—to the context in which that individual lives: human enhancement is something done to or with a particular person in a fixed set of circumstances, namely, a change in her or his biology or psychology. This choice already predisposes the debate and research on enhancement with respect to adapting an individual to her or his environment.

To provide an illustrative and provocative counterexample: under this definition the “treatment” of a homosexual suffering from social exclusion by instigating heterosexual acts and relations, as was routinely performed by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists until the 1970s (Barlow 1973; Hinrichsen & Katahn 1975), would qualify as a form of human enhancement—inasmuch as it succeeds in “helping” the subject to avoid the undesired sexual behaviour that instigates social exclusion and the suffering probably caused by it. With respect to this historical example we already know that leading psychiatrists later acknowledged that there was nothing inherently wrong with homosexuals, but that their suffering indeed originated from social exclusion; this reasoning eventually lead to the decision not to consider homosexuality a mental disorder any longer (Friedman et al. 1976). It is instructive to contrast the definition proposed by Savulescu and colleagues with the following inverted alternative.

Human Enhancement-Inverted =Df A change in the relevant set of circumstances that increases the chances of a person to lead a good life according to her or his preferences.

This alternative is not meant to be a logical inversion, but instead switches the levels of intervention, of that which is malleable and that which is considered as given. In an experimental fashion, one could also say that it is about a switch of dependent and independent variables, from the individual to its life context. Yet the aim of the intervention remains unchanged: increasing the chances of leading a good life. It goes without saying that both definitions, when put into practice, are constrained by available means and ethical principles, for example also requiring that we take the likelihood of other people’s chances of leading a good life into account. It is not necessary here to argue that the inverted definition is better than the original; my intention is merely to show that we need not focus on bio-psychological changes alone. Instead, we can target the social context as well, decreasing the risk of adapting people to a social standard. Please note that this in itself does not imply a normative judgment, but rather widens the perspective for further analysis by taking alternative levels of intervention into consideration. As mentioned before, the balance between freedom and coercion, and autonomy and heteronomy will be essential with respect to epigenetic proactivism.

Here I have described some basic assumptions and criticism of the neuroethics debate on human enhancement, including the association of wellbeing with standards developed in clinical contexts that focus on individuals rather than on their social contexts. In the next section I will introduce research aimed at describing and understanding what people themselves consider to be quality of life, which poses an alternative to the standard adapted from clinical psychology.