3 Perceptual presence and counterfactual richness

The second part of Wiese’s commentary picks up on the issue of perceptual presence, which in my target article was associated with the “richness” of counterfactual sensorimotor predictions (see also Seth 2014, 2015b). Wiese makes a number of connected points. First, he rightly notes an ambiguity between objecthood and presence in perceptual phenomenology, as presented in my target article (Seth this collection) and in Seth (2014). Second, he introduces the notion of causal encapsulation as a third phenomenological dimension, complementing counterfactual richness and perspective dependence. He spends some time developing examples based on cognitive phenomenology and mental action to illustrate how these dimensions might relate. Here, I will focus on the relationship between presence and objecthood from the perspective of counterfactual predictive processing – or more specifically the theory of “ Predictive Processing of SensoriMotor Contingencies” (PPSMC; Seth 2014, 2015b).[5]

3.1 Presence and objecthood together

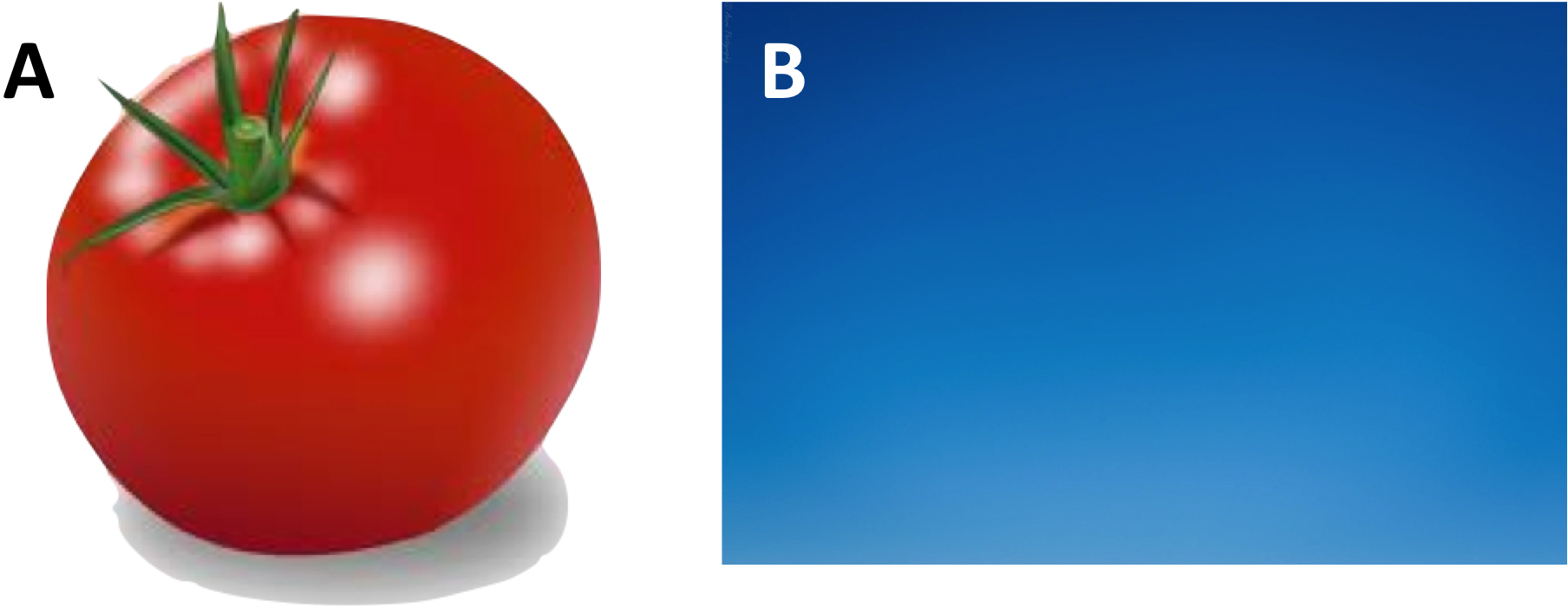

As Wiese notes, when visually perceiving a real tomato (figure 1A) there is both a sense of presence (the subjective sense of reality of the tomato) and of objecthood (the perception that a (real) object is the cause of sensations). Importantly, while distinct, these properties are not independent. There is a “world-revealing” dimension to perceptual presence which is closely aligned with the experience of an externally-existing object: “How can it be true … that we are perceptually aware, when we look at a tomato, of the parts of the tomato which, strictly speaking, we do not perceive. This is the puzzle of perceptual presence” (Noë 2006, p. 414).

Figure 1: A. An image of a tomato. B. An image of a clear blue sky.

Figure 1: A. An image of a tomato. B. An image of a clear blue sky.

How does this object-related world-revealing presence come about? In predictive processing (and by extension PPSMC), objecthood depends on predictive models encoding hierarchically deep invariances that accommodate complex nonlinear mappings from (object-related, world-revealing) hidden causes to sensory signals (Clark 2013; Hohwy 2013). There is a reciprocal dependency here between hierarchical depth and counterfactual richness, because (i) hierarchically deep invariances in generative models enable precise predictions about rich repertoires of counterfactual sensorimotor mappings, and (ii) counterfactual richness can scaffold the acquisition of hierarchically deep invariant predictions. One might even say that hierarchically deep invariances are partly constituted by (possibly latent) predictions of counterfactually rich sensorimotor mappings (Seth 2015b). These dependencies indicate that objecthood and world-revealing presence depend on expectations about counterfactual richness, rather than counterfactual richness per se. Altogether, counterfactually-informed active inference enables the extraction and encoding of hierarchically deep hidden causes of sensory signals. In virtue of hierarchical depth, these inferred causes will also be perspective invariant, in the sense that they will have been separated from those causes that depend on on actions (or other properties) of the perceiver (see Wiese this collection, p. 11). In short, to the extent that objecthood and perceptual presence go together, so do hierarchical depth (encoding world-revealing invariances) and (expected) counterfactual richness.

3.2 Presence and objecthood apart

So far so good, but it is evident that presence and objecthood do not always go together (Di Paolo 2014; Froese 2014; Madary 2014), a phenomenological fact which requires further analysis (Seth 2015b). Presence without objecthood is exemplified in vision by the experience of a uniform deep blue sky (Figure 1B), and is also characteristic of non-visual modalities like olfaction (Madary 2014). The visual impression of a blue sky, or the tang of briny sea air, both seem perceptually present but without eliciting any specific phenomenology of objecthood. At the same time, the corresponding predictive models are likely to be hierarchically shallow and counterfactually poor: there is not much I can do (besides closing my eyes or looking away) to alter the sensory input evoking a blue-sky experience, and the inferred hidden causes are unlikely to lie behind multiple inferential layers. Hierarchical shallowness may explain the lack of phenomenal objecthood, but why isn’t there also a lack of perceptual presence?

Blue-sky-experiences (and olfactory scenes) actually do lack the world-revealing presence associated with objecthood. But they do not appear phenomenally unreal in the sense that perceptual afterimages and synaesthetic concurrents are experienced as unreal. In PPSMC, phenomenal unreality can arise from an inferential failure to separate hidden causes in the world, from those that depend on actions (or other properties) of the perceiver (Seth 2015b). This in turn emerges from violations of counterfactual predictions. For example, consider how saccadic eye movements engage counterfactual predictions. Perceptual afterimages track eye movements, violating counterfactual predictions associated with world-revealing hidden causes that rest on active inference. In contrast, counterfactual predictions associated with blue skies are less amenable to disconfirmation by eye movements, so (non-object-related) perceptual presence remains.[6]

Summarizing, perceptual presence, as an explanatory target, can be refined into (i) a world-revealing presence associated with objecthood and hierarchical depth, and (ii) a phenomenal unreality arising from a failure to inferentially separate hidden causes in the world from those associated with the perceiver. Both rely on counterfactual processing, and so both call on active inference. Perspective invariance is also implicated in objecthood (through hierarchical depth) and phenomenal unreality (through isolating worldy causes), suggesting that this dimension may not be as separable from counterfactual richness as proposed by Wiese (this collection, p. 13). But is that all there is to presence?

3.3 Causal encapsulation and embodiment

Wiese distinguishes three dimensions to perceptual presence: counterfactual richness (vs. poverty), perspective invariance (vs. dependence), and causal encapsulation (vs. integration). The third of these, causal encapsulation, is perhaps the hardest to pin down. The idea as I understand it, is that a representation (predictive model) is causally encapsulated if it is inferentially isolated from other hidden causes; by contrast it is causally open or integrated if it expresses a rich set of relations to other inferred causes. So, a predictive model underlying the experience of a tomato may be causally integrated with that underlying the experience of the table on which it lies, and the hand (maybe my hand), which is poised to reach out and pick it up. Here, there may be a relation between causal encapsulation/integration and the inferential unmixing of perceiver-related and world-related hidden causes: a failure to separate these causes would presumably prevent rich causal integration with other hidden causes in the world.

The concept of causal encapsulation highlights another interesting aspect of Wiese’s commentary: the idea that counterfactual predictions may not always encode sensorimotor contingencies: “it might be equally relevant to encode how sensory signals pertaining to the tomato would change if the wind were to blow … or if the tomato were to fall down” (Wiese this collection, p. 11). While such extra-personal causal contingencies may be salient in many cases, I see them as secondary to sensorimotor body-related counterfactual predictions. By definition they do not involve active inference: I have to wait for the wind to change direction (though perhaps I might move to get a better view). This means that many central features of active inference discussed here – its relation to predictive control, homeostasis, and counterfactually-informed model disambiguation – do not apply.

The body re-emerges here as central, this time as a ground for the generation of counterfactual predictions. Specifically, bodily constraints shape counterfactual predictions since they place limits on how actions can be deployed in intervening upon the (inferred) causes of sensory input. This suggests that changing action repertoires would alter experiences of presence. Wiese raises out-of-body-experiences and dream experiences as a relevant context (this collection, p. 15), where subjects sometimes identify their first-person-perspective, not with a body, but with an unextended point in space. I agree with him that examining world-revealing presence in these situations would be fascinating, if extremely difficult in practice.

The body is of course not only a source of counterfactual predictions, but also the target of counterfactually-informed active inference, both for representation (exemplified by the rubber-hand-illusion, as mentioned by Wiese) and for control.[7] As emphasized in the target article, control-oriented active inference is particularly significant for interoception, where predictive modelling is geared towards allostasis and homeostasis rather than accurate representation (see also Seth 2013). Returning the focus to interoceptive inference raises a host of intriguing questions, which can only gestured at here. One may straightaway wonder how counterfactual aspects of interoceptive inference shape the “presence” of emotional and body-related experiences. Is it possible to have an emotional experience lacking in “affective presence” – and what is the phenomenological correlate of “objecthood” for interoceptive experience? Other interesting questions are how precision weighting sets the balance between representation versus control in active interoceptive inference, and what it means to isolate “wordly” causes when both the means and the targets of active inference are realized in the body. These are not just theoretical questions: advances in virtual reality (Suzuki et al. 2013) and in methods for measuring interoceptive signals (Hallin & Wu 1998) promise real empirical progress on these issues.