3 The self-touching illusion

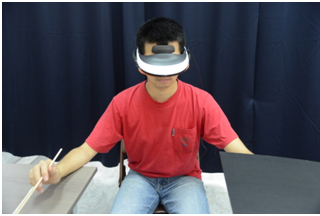

At the end of my target paper I suggested that the next step for the investigation of the sense of self-as-subject would be to study the various conditions where one can pursue the Wittgenstein Question. I recently designed a set of experiments that allow us make exactly this step. The subject wore a head-mounted display (HMD) connected to a stereo camera positioned on the experimenter’s head. Sitting face to face, they used their right hand to hold a paintbrush, and brushed each other’s left hand (figure 1).[4] Through the HMD, the subject adopted the experimenter’s 1PP as if it was his/her own 1PP. In Experiment 1, the participant watched from the adopted 3PP (180°) the front side of his/her own virtual body, including not only the torso, legs, and face, but also his/her own right hand holding a paintbrush (figure 2). In Experiment 2, the participant watched from the adopted 3PP (180°) the front side of his/her own virtual body, including the torso and legs, but not the face. The participant also saw his/her own left hand being touched by a paintbrush held by the experimenter’s hand (figure 3). Compared with the asynchronous condition, the synchronous full-body condition generated a “self-touching illusion”: the subject felt “I was brushing my own hand!”[5]

Figure 1: Experimental set-up.

Figure 1: Experimental set-up.

Figure 2: Subjects’ view via the HMD in Experiment 1.

Figure 2: Subjects’ view via the HMD in Experiment 1.

Figure 3: Subjects’ view via the HMD in Experiment 2.

Figure 3: Subjects’ view via the HMD in Experiment 2.

Two “Wittgenstein Questions” in the questionnaires were designed specifically to measure the participants’ sense of experiential ownership: “It was me who felt being brushed, not someone else” (WQ1), and “The one who felt being brushed was not me” (WQ2). Notice that these two statements are directly opposed to each other. In addition, they are not about the sense of body ownership, but about who felt the tactile sensations caused by brushing. In Experiments 1 and 2, the participants were touched by a paintbrush, so they were indeed the subjects of those tactile sensations. This fixed the fact of their experiential ownership. The task was to examine whether this fact was correctly represented by their sense of experiential ownership. Focusing on the synchronous conditions, the average scores on WQ1 were 1.58 and 1.04 in Experiments 1 and 2 respectively, and the average scores on WQ2 were -1.03 and -0.50 in Experiments 1 and 2 respectively.

Suppose that the participants understood WQ1 as addressing themselves. That is, from their subjective point of view: it was me who felt the brushing. Then, according to IEM, no participants would commit mistakes regarding their sense of experiential ownership. One would expect that most participants would answer “strongly agree” (+3) or at least “agree” (+2) on WQ1. But that is not the case. In fact, 13.2% of participants in the synchronous conditions of Experiments 1 and 2 disagreed with WQ1 (i.e., they answered either -1, -2, or -3), and the average scores of WQ1 reported above were much lower than this interpretation requires. I discuss other possible interpretations elsewhere and argue that neither of them can support IEM.[6] Based on the data, it is more plausible that at least some participants in these experiments were uncertain and hence prone to error about whether they were the subjects of the tactile sensations that they actually felt. That is, the fact of having tactile sensations does not guarantee that the participants will necessarily have the sense that “I am the one who felt them.”[7] Overall, the data provide empirical evidence for the possibility that one’s sense of experiential ownership can misrepresent the relevant fact of experiential ownership. Hence, IEM could potentially be falsified.