2 Quantification of dream lucidity as subjective experience

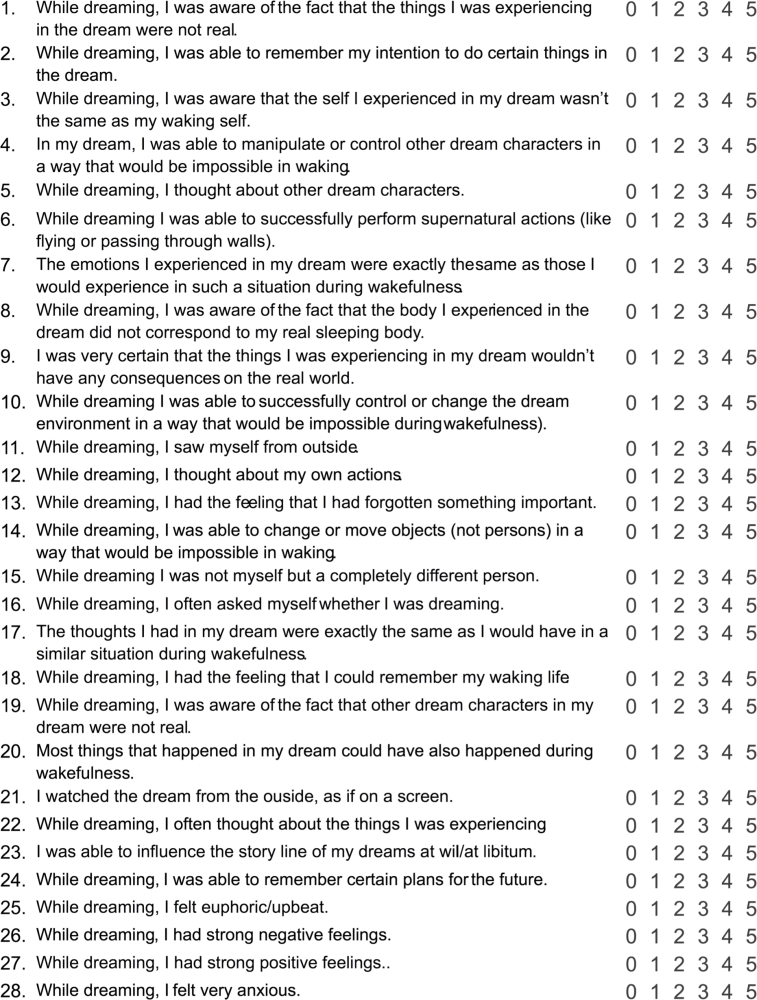

Figure 1: Lucidity in Dreams (LuCiD) scale (adopted from Voss et al.2013).

Figure 1: Lucidity in Dreams (LuCiD) scale (adopted from Voss et al.2013).

Perhaps the most problematic aspect of conducting research into lucid dreaming is the difficulty of obtaining both qualified and quantified evidence of the secondary consciousness in dreams. By secondary consciousness we mean the subjective awareness of our state in dreaming, and particularly meta-awareness, meaning an instance of actively acquired self-knowledge or a sudden insight, regardless whether it is accurate or counterfactual (see Metzinger 2013). Meta-awareness is most clearly manifest in waking consciousness. Dream consciousness, by contrast, is called primary (following Edelman 1992) because while it is both richly perceptual and powerfully emotional, it is weakly cognitive with conspicuous defects in insight (the main focus of this paper) orientation, and memory, though this does not mean that all thinking is missing (Hobson et al. 2011; Kahan & Sullivan 2012; Kahn & Hobson 2005). See Hobson & Voss for detailed discussion of this phenomenology (2010).

Regarding qualification, Hearne (1978) and LaBerge (1980, 1985) took advantage of the fact that humans can be trained to voluntarily move their eyes in Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep and thereby to signal conscious awareness while dreaming. Although care must be taken to minimize the rate of false positive responses, LaBerge’s method has proven quite useful in our own attempts to reliably identify lucid dreaming objectively (Voss et al. 2009).

With respect to quantification, it is important to note that until recently, lucid dreaming was not quantitatively defined. While some authors described lucid dreams in a narrow sense as dreams in which one knows that one is currently dreaming (LaBerge 1985; LaBerge & Gackenbach 2000), others subscribed to a broader definition of lucidity as an all-pervading experiential phenomenon, which is purportedly characterized not only by reflective insight into the fact that one is currently dreaming, but also by full intellectual clarity including: the availability of autobiographic memory sources, the ability to actively control the dream, as well as an overall increase in the intensity of multimodal hallucinatory imagery. This state is often described as taking on a hyper-real quality (Tart 1988; Metzinger 2003; Windt & Metzinger 2007). While sharing an interest in the broader definition, we restrict our attention here to the narrower one in which insight into the fact that one is currently dreaming represents the core criterion for lucidity.

In an attempt to be better able to assess the major and minor determinants of dream lucidity, we developed a Lucidity and Consciousness in Dreams Scale (LuCiD) which was based on hypotheses derived from theory and which we analysed and validated using factor-analysis (Voss et al. 2013). The LuCiD scale presents an important step towards shedding light on the relationship between lucid dreams and other types of dreaming, as well as on the evaluation of cognition in the dream state and its relationship to other aspects of dreaming, such as the intensity of hallucinatory imagery and dream control.

The scale items were constructed by an interdisciplinary team of philosophers, psychiatrists, and psychologists. Our results are based on reports of more than 300 non-lucid and lucid dreams, and verified by reports following forced REM sleep awakenings in the laboratory. Our analysis identified eight factors involved in dream consciousness. Although it is of course possible that our initial item pool did not exhaust all theoretically possible elements, we consider these results a first step in the search for an empirical definition of dream consciousness. According to the factor analysis that we performed, lucid dream consciousness can best be described by the factors (1) INSIGHT into the fact that what one is currently experiencing is not real, but is only a dream; (2) a sense of REALISM, pertaining to the similarity between emotions, thoughts and events with wakefulness as judged after awakening from the dream; (3) CONTROL over the dream plot; (4) access to waking MEMORY; (5) THOUGHT about other dream characters; (6) POSITIVE EMOTION; (7) NEGATIVE EMOTION; and (8) DISSOCIATION akin to taking on a third-person perspective (for a copy of the LuCiD scale see Figure 1).

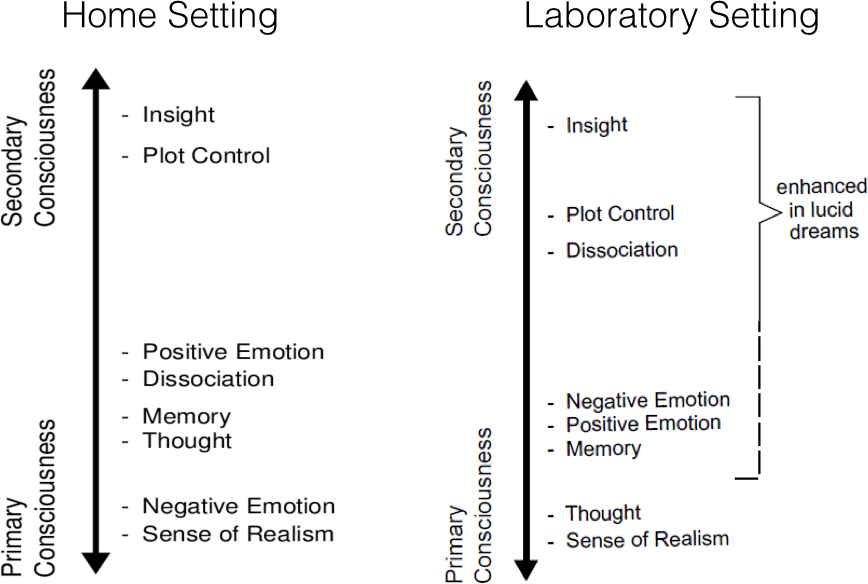

The factor analysis results support both the restricted definition of lucidity that we have adopted and the broader definition utilised by others. The strength of the factor INSIGHT favors the simple definition, while the wide range of other factors (see Figure 2) favors the more complex definition. While both types of definition certainly have their merits, this difficulty in defining lucid dreams brings some important questions to the fore. What, for instance, is the exact relationship between metacognitive insight into the dream state and the hallucinatory quality of the dream (for the relationship between thinking and hallucinations across the sleep-wake cycle, see Fosse et al. 2001)? And how do these aspects of dream lucidity, in turn, influence the ability to engage in deliberate dream control, which fluctuates considerably?

Figure 2: (partially adapted from Voss et al.2014): Positions on the primary to secondary consciousness axis are based on the logarithm of ratios of mean scores in lucid and non-lucid dreams. All factors have been identified as components of dream consciousness.

Figure 2: (partially adapted from Voss et al.2014): Positions on the primary to secondary consciousness axis are based on the logarithm of ratios of mean scores in lucid and non-lucid dreams. All factors have been identified as components of dream consciousness.

a)Rank order of logarithm of mean scores derived from dream reports collected in a home setting. Note that these reports were often recorded in the morning instead of immediately following an awakening from REM sleep. Judging from our admittedly limited experience, these reports are less distorted and more story-like than those following forced awakenings in the laboratory.

b)Rank order of logarithm of mean scores derived from dream reports following forced awakenings from REM sleep in a laboratory setting. Lucid dreams, which are thought to add elements of secondary consciousness, are characterized by increased ratings in reflective INSIGHT, CONTROL over the dream plot, and DISSOCIATION. To a lesser extent, they are accompanied by access to waking MEMORY, as well as NEGATIVE and POSITIVE EMOTIONS.