1 Introduction

Moral philosophy has taken an empirical turn, with experimental results being brought to bear on core questions in moral psychology (e.g., is altruism motivated by empathy?) and normative ethics (e.g., how plausible are the presuppositions of virtue theory?). Some of the recent empirical work also bears on core questions in metaethics. Metaethical questions are varied, but they broadly concern the foundations of moral judgments. What is the basis of such judgments? What, if anything, could render them true? Here I will argue that these questions can be empirically addressed, and longstanding debates between leading metaethical theories may ultimately be settled experimentally. I will describe empirical results that bear on core metaethical questions. I will not present these results in detail here. My goal is programmatic: I seek to establish the empirical tractability of metaethics. Some of the experiments I describe are exploratory pilot studies, presented in an effort to motivate more research. Even with such preliminary results, we will see that some metaethical theories already enjoy greater empirical support than others. I will argue that the best-supported theory at this stage of inquiry is a form of relativist sentimentalism. Defending this position is subsidiary to my primary goal of advertising the value of empirical methods in metaethical theorizing. There has already been an empirical turn in ethics, but metaethics has been less explicitly targeted by these new approaches.

Talking about “an empirical turn” clearly alludes to another turn in the recent history of philosophy: the linguistic turn. When philosophers turned their attention to language, there was an effort to recast philosophical problems as linguistic in nature. A new set of technical tools was brought into the field: formal semantics. Logic has been part of philosophy historically, but after the linguistic turn it was perceived to be an essential component of philosophical training. Just as formal semantics increased philosophical precision with the linguistic turn, empirical methods have dramatically augmented our tool chest, and stubborn debates may begin to give way. The empirical turn is as momentous as the linguistic turn, and perhaps even more so. Formal semantics allowed us to articulate differences between theories, and empirical methods provide new opportunities for theory confirmation. Neither turn rendered traditional approaches to philosophy idle, but rather supplemented them. Within metaethics, this supplementation may offer the best hope of settling which competing theories are true.

In calling for a naturalist metaethics, it is important to avoid confusion with two other views. “Naturalism” is sometimes construed as a metaphysical thesis, and also sometimes as a semantic thesis. Metaphysically, “naturalism” refers to the view that everything that exists belongs to the natural world, as opposed to the non-natural, or supernatural world. This is sometimes presented as a synonym for physicalism, which can be defined as the view that the world described by the physical sciences is complete, in that any physical duplicate of this world would be a duplicate simpliciter. The causal closure of the physical world and the success of physical science are taken as evidence for this metaphysical view. Semantic naturalism attempts to reductively analyze concepts from one domain in terms of another, which is considered more likely to be natural in a metaphysical sense. In philosophy of mind, this might involve defining psychological concepts in neural or causal terms, while in ethics it might involve defining moral properties in terms of psychological, logical, or social terms (such as hedonic states, principles of reason, or social contracts). Here I will be concerned with methodogical naturalism, which has recent roots in the work of W.V.O. Quine, who grew skeptical about philosophizing through linguistic analysis, and emphasized the empricial revisability of philosophical claims (1969). Quine drew on the methods of John Dewey, and insisted that “knowledge, mind, and meaning […] are to be studied in the same empricial spirit that animates nautral science” (1969, p. 26). More succinctly, methodological naturalism can be defined as follows:

Methodological naturalism =Df the view that we should study a domain using empirical methods.

This is the kind of naturalism that has long been advocated, but too rarely followed, in the domain of epistemology (Kornblith 1985). Neither metaphysical nor semantic naturalism are equivalent to methodological naturalism. Metaphysical naturalism is a view about what exists, not about how to study it. Indeed, some non-naturalists in this metaphysical sense believe that empirical methods can be used to study non-physical or supernatural entities. Semantic naturalism is a view about how to state theories (viz., in reductionist terms), but practitioners have rarely used empirical science in defense of such theories (consider so-called naturalistic semantics). Methodological naturalism has been deployed in discussions of both first-order ethics (e.g., Brandt 1959; Flanagan 1991; Doris 1998; Greene 2007) and in metaethics (e.g., Railton 1993; Prinz 2007b). As Railton points out, a naturalist methodology could result in a reductionist theory of morality, but it need not (see also Boyd 1988). In principle, science could support traditional intuitionism, which is not naturalistic in either of these other senses.

1.1 Methodological preamble

Philosophy has always been methodologically pluralistic. Some use intuitions to arrive at necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of concepts (e.g., Plato’s early dialogues). Some try to systematize and revise a large set of beliefs using reflective equilibrium (e.g., Rawls on justice). Some use transcendental arguments to figure out preconditions for thought and action (e.g., Kant). Some use aphorisms or stories to reveal facts about ourselves or to envision possible alternatives (e.g., Nietzsche and the existentialist tradition). Some propose historical analyses of prevailing institutions and values (e.g., Hobbes, Rousseau, and Foucault). Some disclose hidden social forces that buffer prevailing categories (e.g., Marilyn Frye on gender). Some analyze case studies (e.g., Kuhn), probe the structure of experience (e.g., Husserl), or propose formalizations (e.g., Frege). These and other methods suggest that philosophy is a many-splendored thing, and among its many forms one can also find the deployment of empirical results. Examples include Descartes and James on the emotions, Merleau-Ponty on embodiment, and Wittgenstein on aspect perception. Empirical observations have often guided philosophical inquiry. Locke was inspired by corpuscular physics, Marx took solace in Darwinian biology, and Carnap incorporated ideas from behaviorism.

The term “empirical” is used in different ways. In its broadest application, it refers to observational methods. Observation can include an examination of the world, both inner and outer, with and without special instruments. Even introspection can be regarded as a form of observation, as the etymology of the term suggests, and in this sense, the introspection of intuitions is an observational method. Philosophers who use intuitions in theory-construction can be characterised as doing something empirical in this broad sense. Linguistics has used such intuitions to construct syntactic theories, and few would deny that syntax is an empirical field. But the term “empirical” is also used more narrowly to refer to the use of scientific methods, which involve the design of repeatable observation procedures, and the quantification and mathematical analysis of data. The empirical turn in philosophy has been marked by a dramatic increase in the use of scientific results.

Many philosophers have long held a positive attitude toward science, but the frequent use of scientific results (outside of the philosophies of science) is a recent phenomenon. It became popular in naturalized epistemology, which draws on the psychology of decision-making, and philosophy of mind, which has drawn on psychology, computer science, and artificial intelligence. Over the last decade, empirical methods have also become widely used, and widely contested, in ethics.

The resistance to empirical methods in ethics is often chalked up to the fact that ethics is a normative domain, and empirical methods provide descriptive results. This can only be part of the story, however, as there has been little uptake of empirical methods in metaethics. Metaethics is a descriptive domain; it does not tell us how to act morally, but rather explores the semantic commitments and metaphysical foundations of such claims. I suspect the reason for resistance is less interesting and more sociological. Psychology is a young profession, which grew out of philosophy and physiology but then acquired its own institutional standing in the academy, and it has had to fiercely guard its status as a science by distancing itself from the humanities. Meanwhile, philosophy underwent an analytic turn, which led to a preoccupation with conceptual analysis, and an anxiety about psychologism. On this vision, the field began to model itself on logic or mathematics, which were, in turn, taken to be a priori domains. I think this is a fundamental mistake. In many domains, the concepts that matter most are grounded in human usage, not in a transcendental realm like (allegedly) mathematics. The arbiters of conceptual truth include both the inferences we are inclined to draw and our linguistic behavior, both of which can be studied empirically. I will not argue directly against a priori approaches, but will instead make an empirical case, or better yet an invitation, by attempting to illustrate how empirical findings make contact with traditional philosophical questions in metaethics.

One manifestation of the empirical turn has been the rise of experimental philosophy. This term most often refers to the work of philosophers who conduct studies that probe people’s intuitions about philosophical thought experiments. Strictly speaking, much of this work is not experimental, since the term “experiment” is often reserved in psychological research for studies in which researchers attempt to manipulate the mental states of their participants—experimental conditions are compared against control conditions. Experimental philosophy often explores standing intuitions, rather than the factors that influence those intuitions (e.g., Mikhail 2002). For example, some trolley studies simply poll opinions about the permissability of certain actions. That is a survey rather than an experiment. One can use survey methods to conduct experiments, however. For example, one could conduct a trolley study in which some vignettes use evocative language in an effort to manipulate participants’ emotions. Few experimental philosophy studies do anything like this. Most ask for opinions without manipulating psychological states. Thus, experimental philosophy characteristically examines the content of people’s concepts and beliefs, rather than the underlying psychological processes. In this sense, experimental philosophy is an extension of conceptual analysis. For those interestested in underlying processes, it can, to this extent, be of limited interest. Some experimental philosophy has also been criticized for failing to meet standards of reliable behavioral reseach (Woolfolk 2013). That said, conceptual questions are often important for philosophical theorizing, and methodological problems with experimental philosophy can be addressed by conducting better and better experiments. Often the first efforts (including much of the work I will describe below) are best regarded as analagous to pilot studies, in need of refinement but successful enough to warrant more careful investigation. In addition, many philosophers draw on (and increasingly conduct) studies that qualify as genuine experiments and meet the standards of good social science. There is a long tradition of philosophers using research published in social science journals to defend philosophical positions. For those who find paradigm cases of experimental philosophy too limiting (because they are based on conceptual intuitions or fail to meet certain standards), there are many other empirical results that can provide illumination. The term “empirical philosophy” can be used as a broader label to cover both opinion polls and experimental manipulations. As I use the term, it refers to the use of scientific results, whether obtained by a philosopher or not, to address philosophical questions. The empirical turn should not be dismissed as philosophy-through-opinion-polls; it is a multi-pronged effort advance philosophical debates by drawing upon observational methods of any kind.

The motivations for the empirical turn are varied, but the most general impetus is the belief that some questions cannot be resolved by more traditional philosophical methods. For example, philosophers interested in the physical basis of consciousness cannot rely on introspection or on an analysis of the concept “conscious.” And even those interested in analysis of concepts have worried about the limits of introspection. There are basically three different theories of what concepts are: Platonic entities, emergent features of linguistic practice, or psychological states. None of these can be completely investigated by introspection. Even psychological states can be difficult to introspect, because much mental activity is unconscious, and because introspection may be prone to error and bias. Moreover, even if a philosopher could perfectly introspect her own concepts, she would not know thereby that others shared the same concepts, and this would greatly limit the scope of her theories. Some experimental philosophers have argued that philosophers’ intuitions are not shared by laypeople. When philosophers and laypeople do agree on intuitions, there is still no guarantee that these accurately reflect reality. For example, most people (at least in the West) find it intuitively plausible that human action derives from character traits, but some empirical philosophers (most notably Owen Flanagan, John Doris, and Gilbert Harman) have drawn attention to psychological research that challenges this assumption.

Traditional and empirical approaches to philosophy are sometimes placed in opposition, but they can also be regarded as interdependent. On one division of labor, traditional methods are used to pose questions and to devise theories that might answer those questions. Empirical methods can then be used to test these theories. This is an over-simplification, of course, because observations can inspire theories, and traditional methods can sometimes refute theories (Gettier cases are a parade example in epistemology), but the proposed division of labor is a decent approximation. Traditional methods have limited testing power because theoretical posits are often difficult to directly observe, and empirical methods have limited power in constructing theories, because theories outstrip evidence. In what follows I will test theories derived from philosophical reflection against the tribunal of empirical evidence.

1.2 A roadmap to metaethics

Let us turn now to the focus of discussion: metaethics. Metaethical questions concern the nature of the moral domain. Metaethicists ask: what kinds of things are we talking about when we make moral judgements? Put differently, metaethics concerns the truthmakers of moral judgements: what kinds of facts, if any, make moral judgements true? That is a metaphysical question but it is normally approached semantically by exploring what we are semantically committed to when we make moral judgements. Metaethics differs from first-order ethics, which concerns the content, derivation, and application of such judgements.

There are many different metaethical theories, and a complete survey here would be impossible. I will focus on major theories that have emerged over the last two hundred and fifty years, with emphasis on proposals that dominated discussion in the twentieth century. To be clear from the outset, my goal is not to consider specific theories that have been advanced by currently active authors in metaethics. Rather, I will survey broader classes of theories that have been around for some time (decades or centuries) in an effort to establish the relevance of empirical work. An adequate examination of any recent theory would require a narrower focus than I am after here, since each theory makes empirical commitments, if at all, in different places.

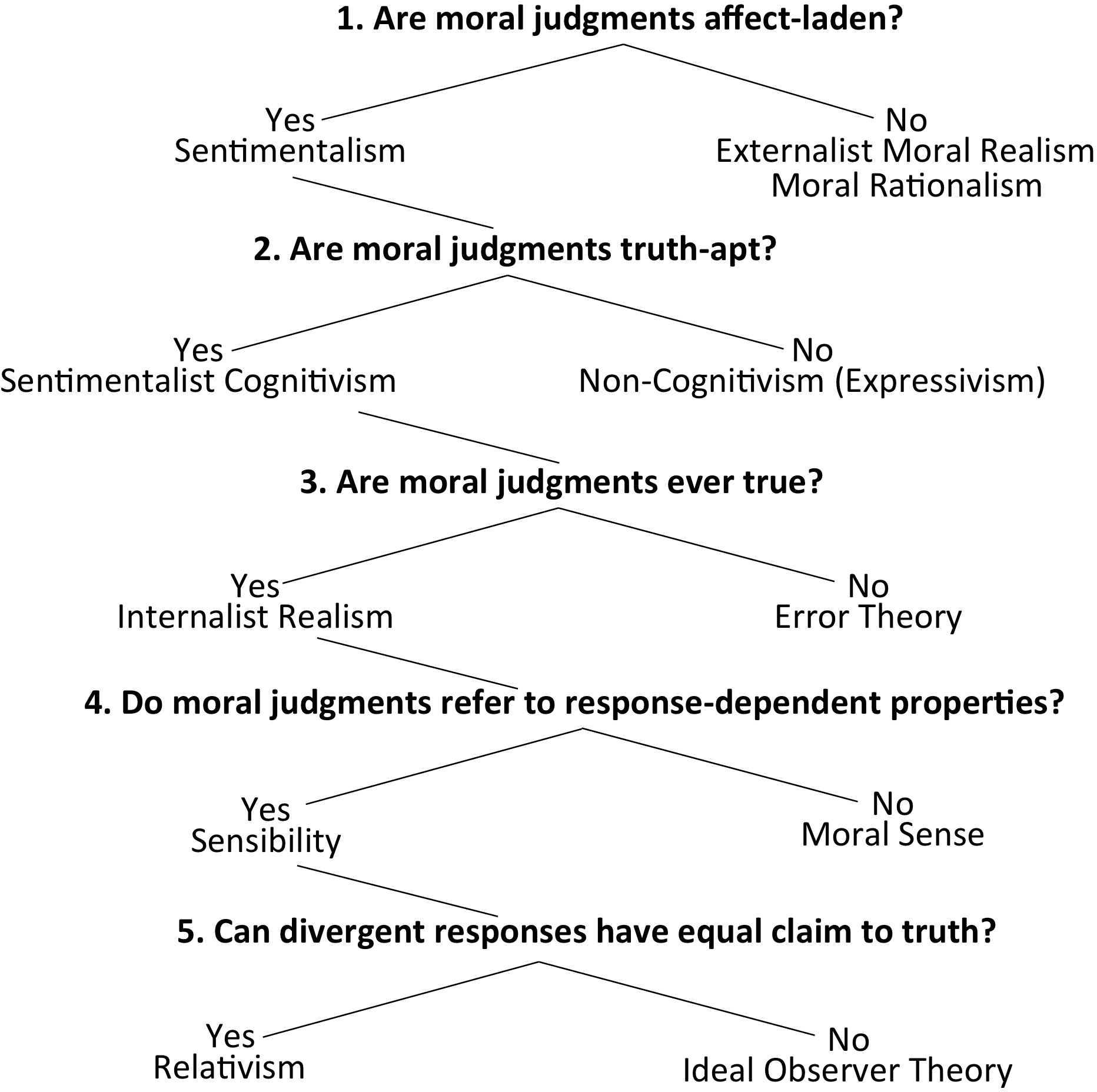

To facilitate discussion, I will map out the theories of interest using a decision tree (Figure 1). The tree could easily be arranged differently. Almost any branch could be the starting place, with other nodes occurring higher or lower than they are in this rendition. As we will see in a moment, I begin with a question about “affect” or emotions. This may seem odd to some contemporary metaethicists. Some contemporary metaethicists discuss emotions (such as Alan Gibbard 1990, and Simon Blackburn 1998), but others do not (for example, emotions are discussed less among moral realists). Historically, however, emotions have been a central focus in metaethics. British moralists, who advanced many of the questions that continue to drive the subfield, often begin their analyses with a discussion of moral sentiments. Indeed, the most famous controversy in metaethics before the twentieth century is probably the dispute between British sentimentalism and Kantian rationalism. Even in the twentieth century, some of the most discussed debates concern emotions, such as the debate between emotivists and their opponents. Moreover, the recent empirical turn was triggered, in part, by discoveries linking emotions to moral judgement. So this starting point has considerable historical depth and great relevance to the methodological sea-change that I am interested in here. That said, I don’t intend this tree to be anything like a complete map of meta-ethics. One could begin elsewhere and branch out in further directions (I expand the tree leftward, but interesting questions also come up on the right). Though incomplete, the nodes of this tree encompass much of what one might cover in an introduction to metaethics in the Anglophone analytic tradition.

Figure 1: A Metaethics decision-tree

Figure 1: A Metaethics decision-tree

The first question in the metaethics decision tree is, I note, a question about emotions. More precisely, we can ask: are moral judgments affect-laden? The term “affect” is used instead of “emotion” here, because it is broader. I intend the term to cover any conative state, such as a preference, desire, or pro-attitude. For most of this discussion, I will focus on emotions rather than these other affective constructs, because emotions are implicated in the empirical work I will be considering.

The other key term in question 1 is “moral judgments.” By “moral judgments” I mean atomic judgments using thin moral concepts, such as wrong, bad, or immoral. The judgment expressed by “Shoplifting is wrong” would be an example. There are many other judgments that arise in moral contexts, including judgments containing thick concepts, such as cruel or unjust. One can also ask whether these are affect-laden. On one analysis, thick concepts are hybrids that have both a descriptive and an evaluative component, the latter of which may implicate the emotions. For the sake of simplicitly I will ignore that debate here.

Notice that judgements are not sentences but rather the thoughts that sentences express. To propose that such thoughts are affect-laden is to say that each token instance involves an emotion or other conative state. There are different forms of “involvement” that have been discussed in metaethics. On some theories, moral judgments contain conative states as constituent parts. This was the view of Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and some other British moralists. One might weaken this by saying that moral judgments do not contain emotions, but refer to them. In this vein, John McDowell, David Wiggins, and Alan Gibbard suggest that moral judgments reflect the conviction or norm that it would be warranted to feel certain emotions. Both of these approaches have gone under the heading “sentimentalism,” with the prefix “neo-” for the views that say the link between moral judgments and emotions is second-order. Here is a definition:

Sentimentalism =Df Moral judgments essentially involve affective states, such as emotions, in one of two ways: such states are constituent parts of moral judgments (traditional sentimentalism); or moral judgments are judgments about the appropriateness of such states (neo-sentimentalism).

Those who deny that moral judgments are affect-laden fall into different categories, but two of the most important metaethical theories of this kind are externalist moral realism and (some forms of) rationalism. Moral realists say that there are moral facts, which is to say that some states of affairs are truly right or wrong (cf. Sayre-McCord 1988). Externalist moral realists add a further requirement, namely mind-independence:

Externalism moral realism =Df There are moral facts and these obtain independently of our recognition of them.

If moral facts are mind-independent, it also follows that we can come to know them without being moved by them. Like scientific facts, we can know that they obtain without feeling any way towards them. Cornell realists, some intuitionists, and many divine command theorists fall into this category. Moral rationalism is a view about how the epistemology or normative status of moral truths:

Moral rationalism =Df Moral truths can be discovered and justified though a purely rational decision procedure.

Kant (1797) is traditionally read this way, though he also claimed that moral judgments involve moral feelings.

The remainder of my metaethics decision tree concerns those who think that moral judgments are affect-laden. Among those who say that moral judgments essentially involve conative states, there is a divide between those who think that moral judgments are nevertheless truth-apt and those who deny this. This is the second division of the tree. A judgment is truth-apt if it is the kind of thing that can be evaluated as true or false. Some affect-laden judgments may turn out to have a merely expressive function. If I say, “Disco sucks!” I may not be attempting to represent a fact, but merely expressing how I feel. Expressivists follow this analogy:

Expressivism =Df Moral assertions express mere feelings or non-assertoric attitudes, and do not purport to convey facts.

Charles Stevenson and A. J. Ayer are credited with devising the emotivist theory of morality, which is the simplest theory of this kind. A more sophisticated variant has been developed by Simon Blackburn, who proposes that moral judgments aspire for quasi-truth, but not truth, and thus an ontologically neutral stand-in—which can explain why moral judgments have an assertoric form. Alan Gibbard says that moral judgments do not directly express feelings, as emotivists claim, but rather express the acceptance of norms according to which feelings such as anger and guilt would be appropriate. All these theories have been broadly classified as expressivist.

Those who say that moral judgments are affect-laden and truth-apt need not deny that moral judgments are expressive, but they insist that they more than express feelings; they assert facts. If so, moral judgments can be true or false. Subjectivism falls into this camp:

Subjectivism =Df the truth of the judgment that something is morally good or bad depends on the feelings or other subjective states of someone who makes that judgment.

For instance, one might propose that “killing is wrong” means “I disapprove of killing.” That judgment is true, if the speaker disapproves of killing, and false otherwise. As we will see, there are also more sophisticated forms of subjectivism. Subjectivists are internalist moral realists: they believe in moral facts, but they deny that those facts obtain independently of our attitudes.

The term “cognitivism” has been used to refer to any view on which moral judgments are truth-apt, which is to say they can be assessed for truth. Expressivists are non-cognitivists, and both subjectivists and external moral realists are cognitivists. One could also have a cognitivist theory and nevertheless insist that all moral judgments are false. This would be an error theory.

Error theory =Df Moral judgments are truth-apt, but they are never true.

The most famous error theory comes from J. L. Mackie. Mackie argues that moral judgments are incoherent. On the one hand, they presuppose that moral facts are objective, which is to say mind-independent. On the other hand, moral judgments presuppose that moral facts are action guiding, and that suggests that they directly motivate us. This suggests that moral judgments must be affect-laden, or otherwise dependent on our subjective states. Since nothing can be both objective and subjective, moral judgments can never be true. Opponents of the error theory deny this and insist that some moral judgments are true. They are, in this sense, moral realists. Moral realists who also claim that moral judgments are affect-laden must take Mackie’s challenge head on, showing that truth is compatible with being action-guiding.

Such sentimentalist realists face an immediate question. They can accept Mackie’s claim that moral judgments represent objective properties, and find some way to circumvent the incoherence, or they could say that moral judgments refer to properties that are subjective, or response-dependent. The first option might seem untenable, since it accepts that moral judgments are both objective and subjective, an apparent contradiction. But the contradiction can be mitigated by distinguishing between sense and reference. One might say that moral concepts have affect-laden senses—that is, we grasp them by means of feeling—and objective referents. Consider, for example, Kant’s aesthetics, according to which beauty consists in a kind of purposeful purposelessness that causes a free-play of the understanding, which results in aesthetic pleasure. A work may have purposeful purposelessness without our recognizing that this is so, but when we recognize it, we feel a certain way. Within ethics, Francis Hutcheson may have held a view that was objectivist and subjectivist in just this way. He suggests that moral facts are established by divine command, but God has furnished us with a moral sense, and that sense works by means of the emotions; when we see objectively bad actions, we feel disapprobation. This has been called a moral sense theory, because it treats our moral passions as a kind of sensory capacity that picks up on real moral facts.

In contrast to this view, one might argue that moral facts are not objective, as Mackie has maintained, but rather are dependent on our responses. This need not imply that moral judgments are mere expressions of feeling; one might say instead that moral judgments refer to response-dependent properties. The idea of response-dependent properties derives from John Locke’s notion of secondary qualities. Primary qualities, such as shape, for Locke, exist independently of being perceived, whereas secondary qualities consist in the power that certain things have to cause responses in us. Colors, for Locke, are not out there in the world, but consist in the fact that objects cause certain sensations in us. The moral analogue of this view has been called the sensibility theory, and its adherents include John McDowell, David Wiggins, and David McNaughton. They resist the causal language found in Locke’s theory of colors, but say something close:

Sensibility theory =Df moral properties are those that warrant moral emotions.

Strictly speaking, the sensibility theory is a form of subjectivism, since it says that moral judgments refer to subjective properties (the property of warranting moral emotions), but the notion of warrant allows these theorists to avoid a pitfall or simple subjectivism. For a simple subjectivist it makes no sense to wonder whether something that I disapprove of is really wrong, but for the sensibility theories I can entertain such doubt because I can wonder whether an event really warrants what I happen to feel. The notion of warrant here is not unproblematic, and it often goes unanalyzed. There is one notable exception, however, and that is the ideal observer theory (Firth 1952; Brandt 1959):

Ideal observer theory =Df The morally good or bad is that which an observer would regard as good or bad under ideal circumstances.

Such circumstances might involve acquiring the status of a moral sage (or consulting a moral sage), as on some virtue theoretic theories, or an ideal version of myself (Smith 1994). Ideal observer theorists are committed to response-dependence; they say that responses determine moral truth, and they further require that those responses come from certain kinds of epistemic agents.

Ideal observer theories offer a negative answer to the final question in the metaethics decision tree. They specify conditions of ideal observation in order to find an authoritative set of responses among a diversity of moral opinions. The hope is that one set of judgments will emerge as epistemically superior to all others; on this view, all moral judges converge under ideal conditions. Here, moral truths work out to be universal. This, of course, is a controversial claim. Suppose we define ideal observers as those who are free from bias, aware of pertinent non-moral facts, and reasoning carefully. It could turn out that, two such observers could still disagree on moral matters. This prognosis leads toward the view that there is no way to arrive at moral consensus. Those who think that moral judgments are rendered true by a judge’s response but deny consensus under optimal epistemic conditions end up saying that moral judgments are relative. This view can be stated as follows:

Metaethical relativism =Df Two judgments expressed using tokens of the same word types, and grasped by tokens of the same mental attitude types can have different truth-values if they are made by different observers.

I will now try to show that each question on the decision tree can be empirically illuminated. Some of the empirical results that I will present come from unpublished, exploratory studies. My goal here is not a detailed documentation of scientific findings, but rather to establish, by means of example, ways in which empirical methods might be brought to bear on the foregoing questions. The hope is that the studies described here might be taken up by others and improved upon.