2 Apparent motion (AM)

I thank Axel Kohler for bringing up AM (apparent motion) as an example of how seminal an illusion can be for research. I do concur that it continues to be a fascinating phenomenon. However, I believe that AM did not fascinate Wertheimer (1912) because it is an illusiond, but rather because it is predominantly an illusionm. Note that the timing has to be just so (i.e., a particular combination of on-times and ISI, inter-stimuli-intervals) in order to perceive what he called phi-motion: perfectly smooth motion practically indistinguishable from real motion. Most of his experiments and demonstrations have in fact worked with suboptimal cases in which the perceived motion is bumpy or faint. In all these other cases of AM, the illusory nature of the percept becomes manifest. The bistable quartet is another beautiful case of an illusionm. The mere fact that the percept can flip at will shows the illusionm to be manifest.

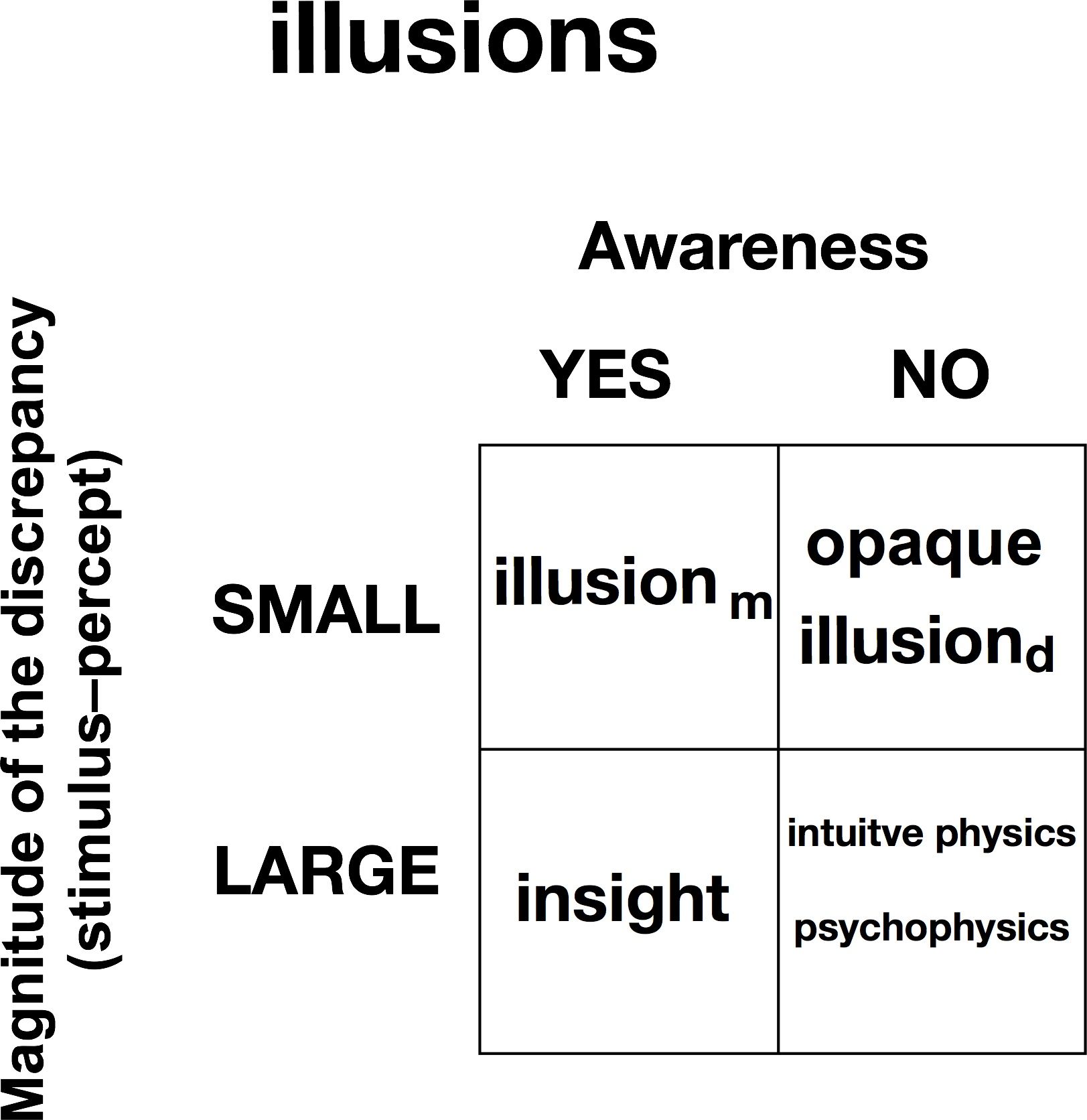

Figure 1: Varieties of illusions.

Figure 1: Varieties of illusions.

As an aside, the Gestalt laws can be understood as an attempt to describe how the percept emerges from the given physical stimulus. But note that while the percept is always different from the physical stimulus, it should not be thought of as illusory just because it is the outcome of a Gestalt process. When I said that Gestalt psychologists have “avoided the term illusion” I was not expecting anyone to count the occurrences of the term in Wertheimer's 1912 paper. He did use the term. I stand corrected. Note, however, that he put the term “Täuschung” in quotation marks the first time he used it, well aware that the phenomenal experience of motion is what makes the Gestalt, regardless of how it relates to the physical stimulus.

Another revealing aspect of AM is its power to reveal the extent to which world-knowledge is factored into our perception, unconsciously and the more so the less well-defined the stimulus. Let us consider a classic AM-display in which two rectangles at two locations and at different orientations are shown in alternation. Whenever the ISI is short (say 100ms), we see one rectangle moving on a straight path and changing its orientation concurrently. If, however, the ISI is lengthened (to, say, 500ms), then the AM-path curves (see McBeath & Shepard 1989; Hecht & Proffitt 1991). The phenomenal quality of this motion is rather ephemeral. We immediately see that the motion is not distinct but fraught with uncertainty. When choosing intermediate ISI, and forcing observers to make up their minds, some observers will see the rectangle curve and others will see it move along a straight path. And when the display remains unchanged but the area between the rectangles is shaded, then the rectangle appears to move along the shaded path. Thus, one can direct the motion of the rectangle along almost arbitrary paths (e.g., Shepard & Zare 1983). Such demonstrations reveal that the very notion of error or discrepancy between physical stimulus and percept becomes shaky. It seems rather arbitrary whether the researcher considers only the rectangles to be the relevant stimulus or also considers the background to be part of the stimulus. In these AM displays, the visual system appears to make sense of the entire display, not just the two moving rectangles.