2 Applying perspective shifts to conceptualizing human experience from the first- versus third-person perspective

The striking parallels between perceptual and conceptual perspective shifts exemplify the embodiment of mental capacities in physical experience (Schubert & Semin 2009). Colloquially, when we talk about dramatic shifts in conceptual understanding, we routinely use perceptual metaphors (Schooler et al. 1994). We speak of “thinking out of the box,” or of “stepping back and looking at the bigger picture.” Even the term that we use for gaining a fresh perspective on an old problem, i.e., “insight,” directly alludes to the parallels between perceptual and conceptual perspective shifting. It is no coincidence that the Gestalt psychologists who pioneered research on visual perspective shifting (Wagemans et al. 2012) also were the first to investigate the processes of conceptual insight (Duncker 1945). And indeed, research in our lab (Schooler & Melcher 1995) reveals a strong correlation between people’s ability to make perceptual insights (e.g., recognizing out-of-focus pictures) and conceptual insights (e.g., solving insight word problems). Thus, in order to explore how perspective may constrain our conceptual understandings, it is helpful to start by briefly considering the ways in which perspective can influence perceptual experiences. As will be argued, the manner in which alternative first-person perceptual perspectives constrain our experiences, provides a compelling metaphor for the broader contrast between first- and third-person perspectives that individuals face in reconciling their personal subjective experiences with objective reality.

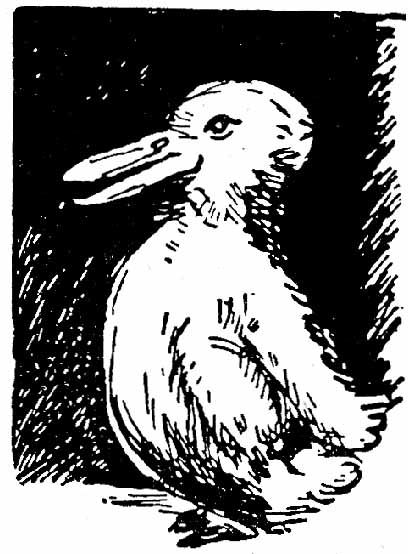

Figure 2: The duck-rabbit illusion is a classic example of a perspective-dependent reversible image. When presented as a duck, those unfamiliar with the image may initially see only a duck. However, if alerted to the possibility of another embedded image, suddenly a rabbit may pop out. McManus, I. C., Freegard, M., Moore, J., & Rawles, R. (2010). Science in the making: Right hand, left hand. II: The duck–rabbit figure. Laterality, 15, 167.

Figure 2: The duck-rabbit illusion is a classic example of a perspective-dependent reversible image. When presented as a duck, those unfamiliar with the image may initially see only a duck. However, if alerted to the possibility of another embedded image, suddenly a rabbit may pop out. McManus, I. C., Freegard, M., Moore, J., & Rawles, R. (2010). Science in the making: Right hand, left hand. II: The duck–rabbit figure. Laterality, 15, 167.

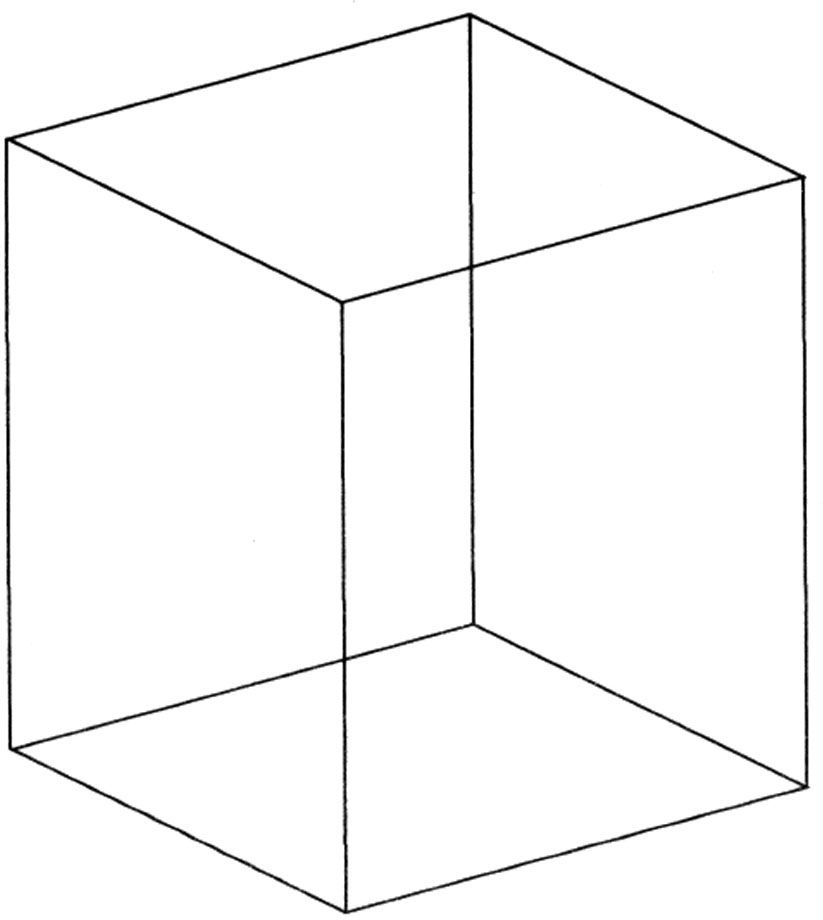

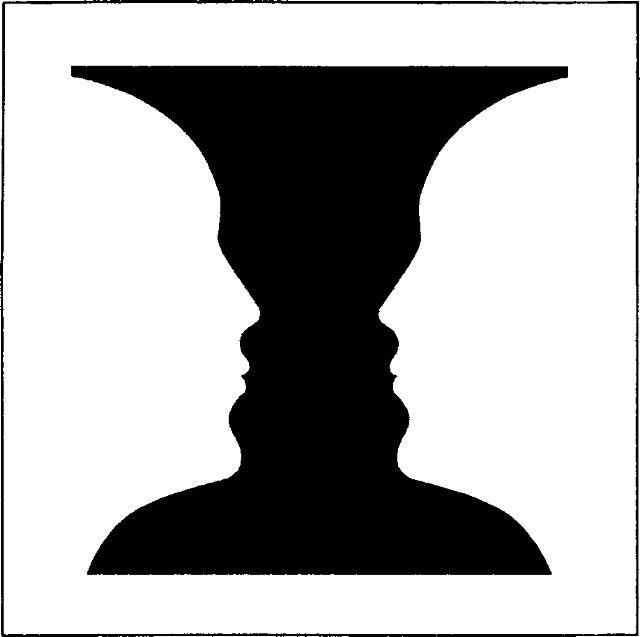

One of the greatest challenges of visual perspective is recognizing how fluid it really is. Typically, when we view an object or a scene, we apprehend it from a particular vantage and rarely consider the possibility that it may be seen in a different way. If and when a shift occurs, the experience is typically characterized by a marked surprise that the very same view could afford such a different understanding. The Gestalt reversible figures are a quintessential example of images that startle us with their alternative perspectives. At first when we encounter them we often perceive them from only one perspective; that is, although there are several possible interpretations of the image, we assign one set of perceptual properties to the elements of the image (front or back, figure or ground), and one conceptual interpretation of the object (e.g., duck or rabbit, young woman or old hag). When presented with an image of a duck/rabbit as a duck, those unfamiliar with the image may initially see only a duck. However, if alerted to the possibility of another embedded image, suddenly a rabbit may virtually pop out. Other classic examples of reversible images include: a Necker cube facing one way or another, a vase or a pair of faces, a young woman or an old hag. A particularly compelling recent addition is the spinning dancer illusion, where a perceptual shift not only changes one’s perspective of her orientation but also the direction in which she appears to be spinning.

Figure 3: The Necker cube is a reversible image that, depending on the perspective taken by the observer, appears to be facing one way or another. Shifting one’s perspective allows the observer to view the cube either from slightly above or slightly below. Necker, L.A. (1832). Observations on some remarkable optical phenomenon seen in Switzerland; and on an optical phenomenon which occurs on viewing a figure of a crystal or geometrical solid. London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 1 (5), 329–337.

Figure 3: The Necker cube is a reversible image that, depending on the perspective taken by the observer, appears to be facing one way or another. Shifting one’s perspective allows the observer to view the cube either from slightly above or slightly below. Necker, L.A. (1832). Observations on some remarkable optical phenomenon seen in Switzerland; and on an optical phenomenon which occurs on viewing a figure of a crystal or geometrical solid. London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 1 (5), 329–337.

Figure 4: Rubin’s vase (sometimes referred to as “The Two Face, One Vase Illusion”) depicts the silhouette of a vase in black and the profiles of two inward-looking faces in white. The figure-ground distinction made by the brain during visual perception determines which image is seen. Ittelson, W. H. (1969). Visual Space Perception, Springer Publishing Company, LOCCCN 60-15818

Figure 4: Rubin’s vase (sometimes referred to as “The Two Face, One Vase Illusion”) depicts the silhouette of a vase in black and the profiles of two inward-looking faces in white. The figure-ground distinction made by the brain during visual perception determines which image is seen. Ittelson, W. H. (1969). Visual Space Perception, Springer Publishing Company, LOCCCN 60-15818

There are several notable aspects of all the aforementioned visual perspective shifting examples. First, before one knows that there are multiple interpretations, it is common to only perceive one or the other. Second, once one is aware of both perspectives, one can experience an oscillation between the two, shifting from one perspective to the other, and back again. Third, at any one moment in time, it is impossible to simultaneously see both interpretations. The Necker cube is either seen facing one way or the other; the spinning dancer only rotates in one direction at a time. Finally, although one can only perceive one interpretation at a time, one can nevertheless know that multiple perspectives exist, and this knowledge provides a meta-perspective, whereby we appreciate that what we perceive one way at one moment can be perceived in a very different way in the next.

Figure 5: The young girl-old woman illusion (otherwise known as “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law”) is a reversible image in which the viewer may either observe a young girl with her head turned to the right or an old woman with a large nose and protruding chin, depending on one’s perspective. Wright, E. (1992) The original of E. G. Boring’s Young Girl/Mother-in-Law drawing and its relation to the pattern of a joke. Perception, 21, 273–275.

Figure 5: The young girl-old woman illusion (otherwise known as “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law”) is a reversible image in which the viewer may either observe a young girl with her head turned to the right or an old woman with a large nose and protruding chin, depending on one’s perspective. Wright, E. (1992) The original of E. G. Boring’s Young Girl/Mother-in-Law drawing and its relation to the pattern of a joke. Perception, 21, 273–275.

A particularly remarkable class of perceptual shift that enables us to switch to a meta-perspective comes from “Magic Eye” stereograms that can reveal a full holographic three-dimensional realm that is not initially perceptible at all. These stereograms entail images that first are viewed as a two-dimensional pattern. However, if one stares at the image long enough in just the right way (this requires a little eye crossing) and believes that it is possible to actually see into it, an entirely different and fully three-dimensional image emerges. What is so striking about these “Magic Eye” stereograms is that the embedded three-dimensional images have absolutely no resemblance to the two-dimensional images from which they emerge. There is of course a sophisticated algorithm (based on principles of stereopsis) that enables the three-dimensional perception to arise from the two-dimensional image, but the experiences of the two images are wholly of a different sort. Those who have not gotten into a Magic Eye image can have no idea what the underlying image looks like, and even if they are shown what the form is, they cannot appreciate what it is like to actually witness the two-dimensional page miraculously open up into a three-dimensional world that is somehow residing within it. However, those who have experienced this transformation gain a wholly different appreciation for the image, recognizing that it affords two entirely different vantages, even while appreciating that only one can be apprehended at any particular time.[1]

The lessons learned from perceptual perspective shifting are relevant to the long-standing tension between conceptualizing human experience from the first- versus third-person perspective. Not unlike the shifting perspectives of a reversible image, the field of psychology has vacillated back and forth between focusing on people’s self-reported internal experiences (the first-person perspective) and their observable behaviors (the third-person perspective). Moreover, just as the spinning dancer can move in one direction for a while, then flip back and forth in direction, and then carry on in the opposite direction, the field has had periods of relative steady focus on one or the other vantage and other periods in which the vantage was more variable.

Figure 6: The spinning dancer illusion, or silhouette illusion, depicts a woman spinning in a circle. The direction of the dancer’s spinning (clockwise or counterclockwise) is dependent on the perspective taken by the observer. Kayahara, Nobuyuki (2003). Silhouette Illusion. ProCreo. Retrieved from http://www.procreo.jp/labo/labo13.html. Click here to see the dynamic version of this demonstration (required on some eBook-Readers and for Google Chrome).

The inception of psychology was marked by a concern with the inner experience of the individual (Schultz & Schultz 1992). Introspection was the tool of choice, and research entailed asking participants to scrutinize the components of their experiences. In short, psychology began with a fixed first-person perspective. In fact, it was during this time that psychology created some of its most robust laws of psychophysics demonstrating strikingly rigorous relationships between changes in various perceptual estimates (e.g., perceived brightness, weight, volume) and changes in the physical stimuli themselves (for a history, see Murray 1993). Then, concerns about the value of introspection arose, and researchers began to vacillate regarding the value of introspection relative to more “objective” third-person perspectives. Although some researchers (notably the Gestalt psychologists and other researchers in the domain of human perception, e.g., Katz 1925/1989) continued to maintain a concern with inner experience, for a significant period of time the behaviorist reign caused a shift toward disregarding people’s first-person perspectives. Internal experience was a taboo topic. In short, psychology switched to a fixed third-person perspective. Then, with the rise of information processing and the cognitive era, the field again began to vacillate back and forth between considering people’s internal experiences and focusing on their behavior.

Figure 7: “Magic Eye” stereograms can reveal a holographic three dimensional realm that is not initially perceptible at all. Consisting of abstract visual patterns constructed from an algorithm based on the principles of stereopsis, “Magic Eye” illusions require the viewer to blur their vision for a period of time, thereby revealing a three-dimensional imprint once perspective has shifted. Image provided by eyetricks.com Additional examples can be found at http://www.magiceye.com/3dfun/stwkdisp.shtml.

Figure 7: “Magic Eye” stereograms can reveal a holographic three dimensional realm that is not initially perceptible at all. Consisting of abstract visual patterns constructed from an algorithm based on the principles of stereopsis, “Magic Eye” illusions require the viewer to blur their vision for a period of time, thereby revealing a three-dimensional imprint once perspective has shifted. Image provided by eyetricks.com Additional examples can be found at http://www.magiceye.com/3dfun/stwkdisp.shtml.

Figure 8: The three-dimensional image is a three dimensional yin-yang which the original Magic Eye image would not have revealed without a shift in perspective. The embedded three dimensional image has absolutely no resemblance to the two dimensional image from which it emerges. Image provided by eyetricks.com.

Figure 8: The three-dimensional image is a three dimensional yin-yang which the original Magic Eye image would not have revealed without a shift in perspective. The embedded three dimensional image has absolutely no resemblance to the two dimensional image from which it emerges. Image provided by eyetricks.com.

While psychology again finds itself in an age of flipping perspectives about first- versus third-person accounts, much consternation still arises from this fact. Science in general (Wilber 1998) and psychology in particular (Wallace 2000) still find it challenging to fully integrate subjective experience into their accounts. Just as it is impossible to see a Necker cube simultaneously facing in its alternative directions, so too psychology has struggled to reconcile its vacillation between first- and third-person perspectives. On the one hand, ignoring the inner realm of experience seems to leave out much of “what it is like” to be human (Nagel 1974). On the other hand, researchers are rightly concerned about the validity and meaning of people’s first-person reports (Wilson 2003). With no alternative window into people’s minds, how can we know that their reports accurately correspond to their inner experience? After all, science necessarily relies on mutually agreed-upon observations. So how can we evaluate the first-person perspective that by its very nature eludes such consensus? The challenge is how to translate these first-person experiences into third-person data that can be scientifically investigated. The most straightforward answer of course is simply to ask people about their experience; their observable verbal statements thus become the third- person window onto their first-person experiences. But here we run up against the challenge that caused psychology to abandon the first-person perspective in the first place: How do we know if self-reports line up with first-person experiences without some independent measure of people’s internal states (Bayne this collection)?

Fortunately, self-reports are not the only third-person window into people’s inner experience. We can also examine other behaviors as well as measure physiological and brain activity in order to make reasoned inferences about what individuals are genuinely experiencing. In this manner, we can begin to discern when people are accurately characterizing their internal experience, and when they may be overlooking or distorting key aspects. The approach that I am advocating here is very much in keeping with Dennett’s notion of heterophenomenology (2003) that takes at its starting point the premise that people’s self-reports do not necessarily reflect what they are actually experiencing but rather “what the subject believes to be true about his or her conscious experience” (Dennett 2003, p. 2). Although such an approach refrains from necessarily taking people’s first-person reports on face value, it does not abandon the prospect of making inferences about what people are actually experiencing.[2] Rather it posits that we must evaluate people’s self-reports in light of other third-person measures. As Dennett (1993) puts it:

My suggestion, then, is that if we were to find real goings-on in people's brains that had enough of the ‘defining’ properties of the items that populate their heterophenomenological worlds, we could reasonably propose that we had discovered what they were really talking about—even if they initially resisted the identifications. And if we discovered that the real goings-on bore only a minor resemblance to the heterophenomenological items, we could reasonably declare that people were just mistaken in the beliefs they expressed, in spite of their sincerity. (p. 95)

As will be argued there are at least some situations in which external observers may have better knowledge of a person’s internal state than does the person in question. Moreover, there are some mental states (e.g., mind-wandering) for which the crucial bottleneck in people’s introspective awareness stems not from their capacity to classify the experience, but rather from the fact that people only intermittently take stock of what is going on in their own minds.

In the following section, I review some of the insights about first-person experience that can be gained when it is assessed from a third-person perspective. By adopting a “trust but verify” approach to first-person reports, we not only gain a more objective understanding of subjective states, but also potentially glean a more astute perspective of our own experience.